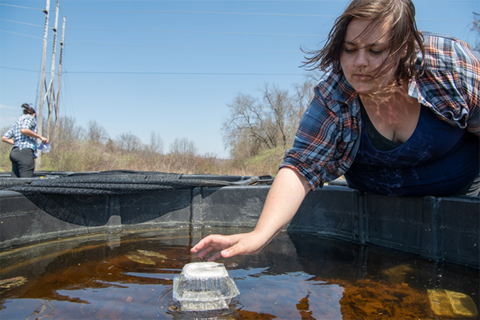

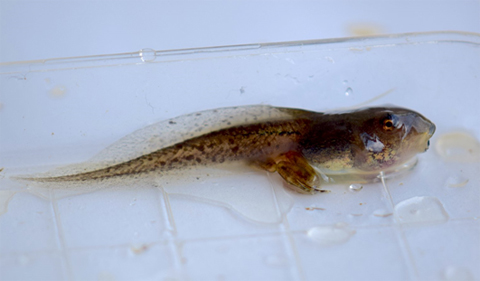

A recently metamorphosed wood frog. Photo by Cassie Thompson.A recently metamorphosed wood frog. Photo by Cassie Thompson.

Ohio University graduate student Cassandra Thompson’s research highlights the need to understand the tradeoffs of using pesticides on invasive species and the effects on vulnerable species such as amphibians.

Her article on “Carryover effects of pesticide exposure and pond drying on performance, behavior, and sex ratios in a pool breeding amphibian” shows several adverse effects from the use of a neonicotinoid (or neonic) pesticide, called imidacloprid, on hemlock trees to kill an invasive aphid called a hemlock wooly adelgid.

Cassandra Thompson checks experimental mesocosms. Thompson studies the synergies between climate change induced effects and predator exposure on wood frog larvae. (photo: Ben Siegel)

But Thompson has some advice for those who want to protect the beautiful eastern hemlocks native to Appalachia from the destructive insects: inject the pesticide into the tree instead of spraying it.

“While imidacloprid can be very helpful in controlling the spread of hemlock wooly adelgid, it can negatively impact local amphibian populations at the aquatic and terrestrial stage causing declines and negative impacts at multiple life stages, Thompson said.

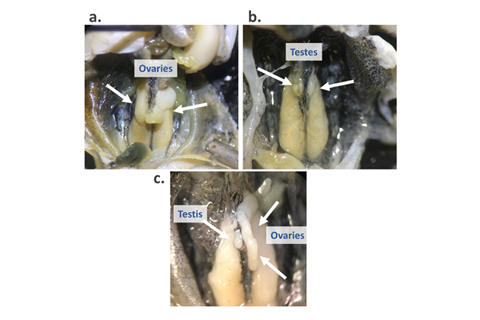

Thompson’s most recent publication documents how tadpole exposure to imidacloprid led to about a 10 percent decrease in males surviving to metamorphosis and a higher proportion of undifferentiated gonads (not clearly male or female), including a hermaphroditic individual.

“Understanding how pesticides like Imidacloprid affect sex ratios give us a better idea of how it may be impacting population dynamics,” Thompson said.

Pictured above are a female (a), male (b), and (c) hermaphroditic (male and female) individuals from the study. Photos and figure by Cassie Thompson.

Thompson: Use Tree Injections Instead of Spraying the Soil

Invasive species can be pervasive and have devastating consequences for native wildlife and the environment.

“If you have hemlock trees in your backyard, you might also have the invasive hemlock wooly adelgid, which is an insect native to East Asia and has been wreaking havoc on hemlocks across the Eastern United States. This is a big deal across Appalachia because eastern hemlocks are considered keystone species in these ecosystems and the death of these trees would mean a big blow to the tourism industry,” Thompson said.

The most common practice to combat hemlock wooly adelgid is through the use of neonicotinoid pesticide called Imidacloprid, which is often sprayed around the base of infected hemlock trees, leading to runoff in local streams and pools, areas where amphibians breed. Imidacloprid can additionally persist in the soil for over 250 days, leading to potential direct contact with juvenile and adult amphibians.

“Luckily we can do something for them. We can manage how we apply this pesticide by using tree injections in place of soil drenching, which not only has more effective and faster uptake of imidacloprid by the hemlock trees, but also minimal to no runoff from soil into nearby bodies of water,” she said.

Undergraduate Megan Sweeney (and co-author) dissecting wood frog metamorphs under dissecting scope. Frogs were dissected in order to assign sex by the presence of ovaries or testes. Photo by Cassie Thompson.

Frogs risk mortality if they settle in ‘drenched’ site

Thompson has been researching wood frog tadpoles for six years and recently finished her Ph.D.in Biological Studies in the College of Arts & Sciences at OHIO in the Ohio Conservation Biology lab working with Dr. Viorel Popescu. Thompson also earned her undergraduate degree, a B.S. in Biological Sciences Wildlife and Conservation in 2015, from the College of Arts & Sciences.

In a previous paper, Thompson found that tadpoles in faster-drying pools responded by metamorphosing more quickly. (See Thompson Discovers Tadpoles Coping with Drier Conditions, Sheds Light on Effects of Climate Change.) The result was smaller frogs who would never catch up in size to frogs that came from slower-drying pools. But their survival rates as juvenile frogs on land were, surprisingly, very similar, although the petite frogs weren’t able to travel as far or as fast as their full-size counterparts.

Her current paper adds another variable—pesticide exposure—to her previous studies of how frogs react to a dryer environment.

“Because amphibians have complex life cycles involving aquatic and terrestrial stages, they have the potential to be exposed to chemical pollutants in both environments. Additionally, exposure to this pesticide may interact with other stressors, such as pond drying and create synergistic or antagonistic effects.” she said.

She set out to test the effects of imidacloprid and pond drying on frogs at both aquatic (tadpole) and terrestrial stages, with particular attention to what happens if juveniles encounter pesticide-treated substrates in terms of both survival and sublethal effects.

To do this, Thompson and her research team raised wood frog tadpoles in experimental ponds on the Ohio University campus and exposed them to a similar level of imidacloprid found as occurs in the wild near sprayed hemlock trees.

Team of undergraduate students and Thompson collecting wood frog tadpoles for measurements at the Aquatic Mesocosm Facility. Photo by Viorel Popescu.

She found that pesticide exposure and pond drying led to fewer individuals surviving to metamorphosis.

“Unexpectedly, we found that frogs from imidacloprid treated tanks were significantly larger than control frogs and prior to exposing them to pesticides in the terrestrial environment, they outperformed control frogs in endurance trials. They may be able to travel further distances and are overall better marathon runners! Unfortunately, they also seem to crash harder,” Thompson said.

“We wanted to know what would happen to a frog if they travel across and temporarily settle in areas that have been recently sprayed with Imidacloprid. After 12-hour exposure to imidacloprid, we found reduced endurance capabilities of frogs from all treatments. Additionally, pre-exposure to imidacloprid as a tadpole caused greater declines in locomotor capability when exposed to imidacloprid again as a recently metamorphosed frog. So if you were exposed as a tadpole and were exposed again in the terrestrial stage, you could have reduced endurance capabilities or how far you can move in the environment,” she said.

Through behavior trials, with frogs from these experimental ponds, Thompson found no evidence that the frogs would avoid areas contaminated with the pesticide.

“If these frogs come across one of these drenched soil sites, they not only won’t be able to behaviorally assess and avoid the pesticide, but also risk mortality if they settle there for a short period as their locomotor abilities will be hampered,” she said.

Thompson’s work is a first step toward understanding the unintended consequences of neonic pesticide application on sensitive amphibians; ongoing and future studies in the OHIO Conservation Biology lab will be addressing questions related to the behavioral effects of Imidacloprid exposure on frogs and to the persistence of the pesticide in the ecosystem after it is uptaken by hemlock trees.

Comments