It’s easy for the tiny seeds to practice social distancing on their flight up to the International Space Station. They’re on an unmanned SpaceX rocket.

But making sure they don’t germinate too early is a problem that has to be solved back on Earth, where Ohio University has asked researchers to work at home.

Ph.D. student Alexander Meyers is getting ready to participate in his third experiment on the International Space Station, this one funded by NASA as part of its Mission to the Moon.

And he has a problem to solve.

The tiny Arabidopsis seeds—so tiny it takes a microscope to place them on the plates that will “fly” into space—are supposed to germinate on the space station, in its low-gravity environment. Not back on Earth or during the rocket trip.

But he’s not supposed to be on campus. So he’s turned his apartment into a temporary germination lab.

Five. Four. Three. Two. One. Germinate.

When they get the call that there’s a space on the next rocket, Meyers and Dr. Sarah Wyatt, Professor of Environmental & Plant Biology, (and likely a few undergraduate students) will head to Kennedy Space Center in Florida. There, in a special lab, they will plate the seeds. And here’s the timeline to beat:

- Late load of the rocket is 48 hours before launch.

- It takes three days for the Dragon capsule to dock with the International Space Station.

- And then the astronauts have to set up the experiment.

That’s at least five days in transit before the seeds can germinate.

From Al’s Refrigerator to the International Space Station

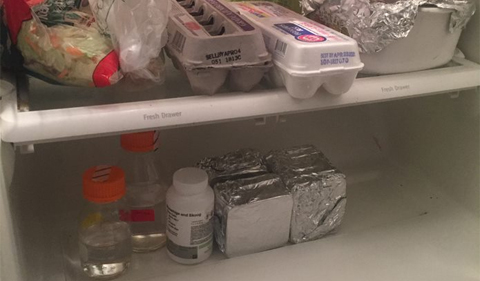

One option Meyers is investigating is whether cold storage will keep the seeds from germinating too early.

Back in the Wyatt lab, they have access to a cold room that keeps a constant temperature.

Meyers has a standard apartment refrigerator.

“That was until he scavenged the little fridge from my office and the simulated ‘Veggie unit’ to complete the lab,” Wyatt says with a smile.

Houston, We Have a Solution

“Some research in our lab can’t go remote because techniques like DNA/RNA extractions require special equipment and potentially hazardous chemicals,” says Wyatt. “Another grad student and an undergrad are working on data analysis by using the VPN to access our data analysis computer, loving named ‘The Mothership.’

“But Al’s remote seedling germination lab is a great example of what we can do if we think a little outside the box (lab). The hardest part was trying to be sure he had everything he needed: plates, membranes, seed, media, forceps, et al. to complete the lab,” she adds.

Let There Be LED Light

Once the seed plates get to the space station, the astronauts will put them in a small growth unit called “the Veggie unit,” with LED lights providing the main ingredient for photosynthesis. Testing the LED lights to see how they affect plant germination is another key part of Meyers’ research.

Back in the Wyatt lab, they have access to a state-of-the-art growth chamber. Meyers has a shelf and some LED lights.

That blue glow in the photo is coming from the simulated Veggie unit that Wyatt and Meyers put together.

Dr. Sarah Wyatt in the real growth lab back on campus a few months ago, with a model of the Falcon rocket that will take their experiment to the International Space Station. Photo by Ben Siegel

“Plants will be a crucial component for astronaut health and well-being during any long-distance spaceflight or colonization mission,” Wyatt said. “They are a source of food, for replenishing water and purifying air as well as physiological and psychological comfort. The challenge is to understand how plants respond to the spaceflight environment to enable plants to thrive in potentially hostile environments.”

Plants don’t grow “up” because they are attracted to sunlight. They grow up because they are responding to gravity. The Wyatt lab is studying the signal-induced gravitropic response in Arabidopsis thaliana.

Meyers recently defended his dissertation in the Ph.D. in Molecular and Cellular Biology program.

For more information on the experiment, see Wyatt Lab Gets Another Ride to Space Station as NASA Preps for Moon Mission.

Comments