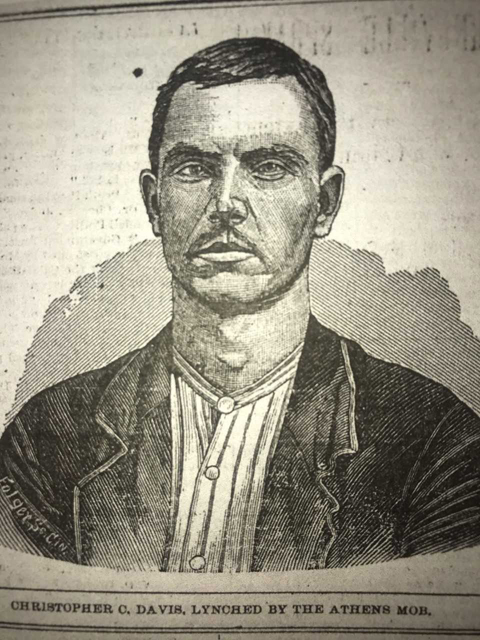

In 1881, Christopher Davis, a biracial man and resident of Athens, was lynched near what is now the Richland Avenue Bridge. Davis, who had a wife, a daughter, and an infant son, had been accused of the rape and attempted murder of Lucinda Luckey, a white woman.

In the years since, with the exception of a very small memorial plaque affixed to the bridge, the tragic account of Davis’ murder has been all but been forgotten in Southeastern Ohio.

Jordan Zdinak, an M.A. student in History, is working on a project that brings Davis’ story to the forefront. With the assistance of Jessica Cyders ’06, Ohio University alumna and Executive Director of the Southeast Ohio History Center, Zdinak curated an exhibit that features newspaper articles, census records, letters, and other materials pertaining to Davis’ murder. Cyders earned a B.A. in History from the College of Arts & Sciences.

The work between Zdinak and the history center marks a particularly significant community-based collaboration: an OHIO student and an area historian working together to teach the Athens community about its history. Zdinak also was mentored by Mary Nally, Director of the Center for Campus and Community Engagement at OHIO.

The exhibit opened Sept. 12 and will be up through the fall at the Southeast Ohio History Center, 24 W. State St., Athens.

“We are consulting with African American historians, including [Appalachian historian and ’61 OHIO alumna] Ada Woodson Adams to help ensure that we display these materials correctly and sensitively,” Zdinak explains.

Zdinak plans to include news accounts that provide conflicting views of Davis’ culpability. Most newspapers blatantly accused Davis of committing the alleged crimes, while one, Meigs County’s Republican, gave evidence for Davis’ innocence. Davis was a resident of Meigs County for most of his life.

“I want to portray the various information that I have found, since there was vastly different reporting not only at the time of the alleged assault but also at the time of the lynching. I want the viewers of the exhibit to think about the biases and prejudice during that time and how this [event] was portrayed in the media, mostly using harsh language like ‘the black beast’ or ‘mulatto ravisher,'” Zdinak states.

The Tragic Account of Christopher Davis

OHIO History Professor Dr. Katherine Jellison introduced Zdinak to some local activists who wanted to spread awareness about the lynching.

“We call ourselves the Christopher Davis Coalition,” Zdinak states.

The coalition contacted the Equal Justice Initiative with a request to fund Davis’ memorial plaque. The Equal Justice Initiative helps to provide memorials nationwide to honor victims of violence, and the organization has agreed to fund the request for Davis’ plaque.

Zdinak explains that in making this request, the coalition needed someone to conduct research on the Davis case.

“With the help of Ada Woodson Adams, I started by looking at the census records. What I learned through my research was shocking,” Zdinak explains.

Luckey and Davis knew each other before she accused him of rape and attempted murder. In fact, Luckey’s house had once caught fire, and she stayed with the Davis family in the aftermath. Davis had also worked as a laborer on Luckey’s land.

On the day of the alleged assault, however, about a year after her temporary residence with the Davis family, Luckey maintained that Davis had visited her home. She had asked him to run an errand for her.

“She asked him to go into town for her to purchase sealing wax,” Zdinak states. “The Meigs County Republican stated that Davis never dropped off the sealing wax at Luckey’s home, though. In fact, the newspaper maintained that the wax was actually found in Davis’ house, so Davis never returned to Luckey’s home on the night of the alleged assault,” she adds.

No formal investigation of any kind took place. In keeping with the overt prejudice of the era, evidenced by the racist and biased language in the newspaper accounts that Zdinak uncovered, Luckey’s allegations were sufficient to warrant Davis’ arrest.

“Davis went to Sabbath School the next day, where he heard about the assault on Luckey. He was arrested when he returned home. He was moved to Chillicothe a few days later for safety because the rumors of a lynching were so widespread. Later, he was moved back to Athens, probably for trial,” Zdinak explains.

On the night of the lynching, several men broke into the Athens Sheriff’s Office, where Davis was jailed. They physically assaulted the sheriff when he refused to give them the cell key, which he had hidden in his pants.

“The men spent an hour breaking into the cell,” Zdinak explains. “It must have been so terrifying for Christopher Davis. Some of the men also held the sheriff’s wife so she couldn’t interfere or attempt to protect Davis. Then they broke into the cell, dragged him to the bridge, and hanged him.”

Though the men who murdered Davis weren’t masked (and were even identified by the sheriff), they faced no punishment or investigation. Two members of the lynch mob included Lucinda Luckey’s son and nephew, Zdinak states.

In terms of Luckey’s alleged assault, Zdinak suspects a possible case of mistaken identity.

“Is it possible that someone who looked like Davis carried out the attack?” she asks.

Exhibit Coinciding with African American Studies Anniversary

Zdinak’s exhibit, “The Lunching of Christopher Davis: A free exhibit on racial injustice and implicit bias,” opened Sept. 12 and will be up through the fall at the Southeast Ohio History Center, 24 W. State St., Athens. The launch coincides with the 50th anniversary of the African American Studies program at OHIO, in addition to OHIO’s Black Alumni Reunion Sept. 14-16.

- See “Groups commemorate 1881 Athens lynching victim” in the Athens Messenger: “Christopher Davis, an Athens County man who was killed in an 1881 lynching while awaiting trial on charges of rape and assault, was honored by several local groups Saturday in an Athens ceremony.”

The exhibit is part of a nationwide effort to contribute to a national database in Alabama, which is collecting soil samples from every location in the United States in which a lynching has been perpetrated.

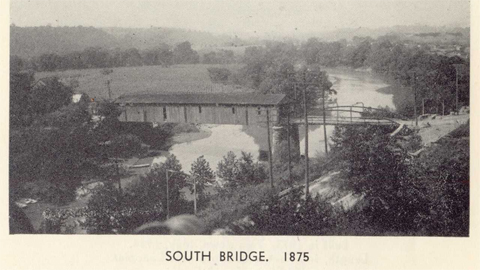

A ceremony to commemorate his life and to collect soil from the site is Saturday, Sept. 14, at the approximate site of his hanging: the base of the old South Bridge.

Confronting Racial Prejudice

In terms of what audiences can learn from the exhibit, Zdinak and Cyders want viewers to think about not only Athens’s past but also its present.

“The biggest goal is to teach people that this happened in Athens,” Cyders states. “Some people think that Athens is immune to racial violence and prejudice, but it’s not. This exhibit is a serious way of showing that. We want to help people realize that, and to consider their own biases,” she adds.

Financial support for the collaboration between Zdinak’s research and the Southeast Ohio History Center is provided in part by a Sugarbush Grant.

One Comment