Spring is here, and love is in the air! The birds are singing, plants are flowering, and insects are pollinating. For Ohio University biologists, it means that nature has entered the spring romantic phase—and it is time to get out into the field.

Undergraduate researcher Madeline Sudnick is in the frontlines, as she is continuing her investigation on how parasitic bird blow flies find romance (potential mates) and egg-laying resources (i.e. baby birds) for their maggots to eat.

Madeline Sudnick, third-year Honors Tutorial College student, setting up a mist net to catch adult birds.

Fly maggots are obligate parasites on baby birds, and they can stress and weaken developing birds, but as a native species, they will often cause little to no injury to the nestlings. This is fine-tuned nature at its best (or worst). However, when parasitic flies are not native, this balance is thrown out of whack, and maggots can severely harm or kill baby birds; this is what is currently happening in the Galapagos, with the famous Darwin’s finches, whose babies are sucked dry by invasive fly maggots.

By studying blow flies in the Ohio system, Sudnick hopes to learn about how parasitic flies communicate and forage—and whether these lessons can be applied to suppress populations of the invasive fly in the Galapagos.

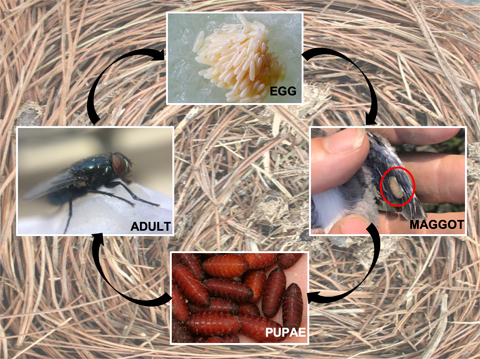

Parasitic bird-blow fly life cycle: Fly egg laying is synchronized with bird hatching; the maggots consume baby bird blood (7-14 days) until the pupa stage where they transform into an adult fly.

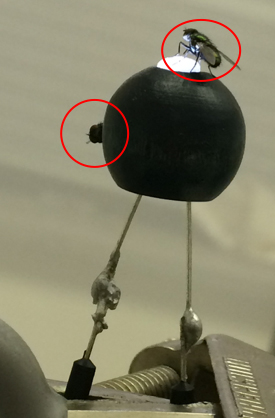

Locating a mate may seem as simple as “swiping right,” but when you are as small as a fly it can be like finding a needle in a haystack. Parasitic adult bird blow flies emerge early in the spring and use their specialized vision to find potential mates. Male flies will guard a territory and identify potential female flies flying through their territory using the light reflected off a female fly’s wings.

These visual cues can be manipulated through LED technology (known as flashing wingbeat frequency) in the lab in a way that scrambles their sophisticated communication system. (See “A Conversation about Sustainable Pest Management” or Science Daily.)

This summer, Sudnick and OHIO researchers will implement this technology for sustainable manipulation and control of parasitic flies in a much more complex field setting, where things can easily go wrong.

Once the adult female fly has mated, she must locate a bird’s nest near the time of the birds hatching in order to give her young enough time to feed. The fly eggs hatch into maggots, which are equipped with “vampire” fangs used to tear into the flesh of the baby birds to access the blood they rely on for meals.

How adult female flies locate a nest of recently hatched birds is still a mystery. Flies are not known to locate hatchlings from chemical substances produced and released from a nest, but likely use sight cues. (Hint: notice what big, beautiful eyes they have!)

Sudnick is no rookie in the field. During the 2018 field season, her preliminary data found that more insulated (taller and heavier) nests, and nests with warmer temperatures around the time of bird hatch were less likely to be parasitized by bird blow flies. So, nest temperature may influence a fly’s ability to locate a nest with hatchlings.

This year, Sudnick and her team will head out into the field again to investigate sight cues associated with temperature.

This research emerged (no pun intended) as a collaboration between Dr. Bekka Brodie and Dr. Kelly Williams in Biological Sciences, as it aims to integrate methods, data, and natural history information across two fields of study: bird ecology and behavior, and insect communication and ecology. This research project has recently garnered $8,000 support from the Ohio University Research Committee to Dr. Williams for the project entitled “Identifying Communication Pathways for Management of Parasitic Bird Blow Flies (Family Protocalliphoridae).”

“This combination of research expertise represents a novel approach in bird and insect ecology” says Brodie, and “has the potential to advance our understanding of bird-insect parasitism, with broad applications for conserving populations of at-risk birds.”

Dr. Williams has been involved with birding groups for >10 years, and through her past avian ecology work, she garnered the support of a broad network of collaborators and volunteers in the Athens area. Capitalizing on this support network, this research project has received financial support though Columbus Audubon, donations made through the Sindisa Fund, and OHIO University Research Council, and community support from Athens Area Birders, Rural Action, and community members like Mike Wren (who provides a field site equipped with over 100 bird boxes!). “Athens, Ohio is a unique place to study this system because everyone is working together, sharing knowledge and offering resource support to create the perfect environment for collecting data, learning, and finding a solution” said Dr. Williams.

As you explore your backyard and your surroundings this spring, take note of the birds nesting and rearing their young, and all the flies mating and looking for places to lay their eggs, and take time to appreciate the complexity of these interactions. In order to breed successfully, birds have to take care of their young. Similarly, bird blow flies need to find a mate and baby birds to lay their eggs on and, if they get their timing right, they will create numerous offspring to start the cycle all over again next spring.

Follow Sudnick on Twitter (@themaddiecology) for LIVE research updates, #OHIOinsects, #VampireMaggots, #SpyingonSongBirds.

Comments