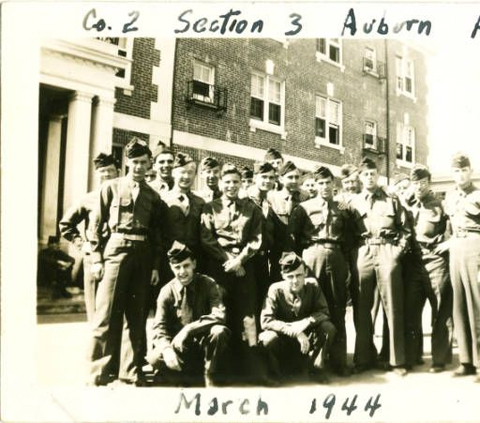

Gifford Doxsee photo from March 1944. From Ohio University Libraries Digital Collections.

Professor Emeritus Gifford Doxsee, age 93, died July 16 in Athens. He was a retired professor of History at Ohio University and a past director of the African Studies program.

He joined the History Department in 1958, teaching European, Middle Eastern, and African history. He retired in 1994.

Doxsee served in the U.S. Army during World War II and was captured during the Battle of the Bulge and held in a Nazi POW camp—Slaughterhouse Five—alongside fellow soldier Kurt Vonnegut, whose novel bore the camp’s name. Doxsee’s life and service is chronicled on his family’s website.

The Gifford B. Doxsee Soviet Russia scrapbook dates from 1940 to 1941 and is part of the Ohio University Libraries Archives and Special Collections. It was created by Doxsee and contains newspaper clippings in English and Russian about political events related to the creation and existence of the Soviet Union. He also authored several books including “Contemporary Egypt: An Assessment of the Revolution” and “Aspect of land use and agrarian reform in Algeria.”

Dr. Gifford Doxsee

Arrangements will be announced by Jagers & Sons Funeral Home.

Doxsee wrote the following autobiography for the American Ex-Prisoners of War:

I was born on Long Island, New York, on July 4, 1924, attended public schools in Freeport, NY, and graduated from Freeport High School in 1942. I enlisted in the Army Reserve on November 13, 1942 while a freshman at Hobart College, Geneva, NY, and was called to active duty June 9, 1943. I received Infantry Basic Training at For McClellan, Anniston, Alabama, during the summer of 1943 and in September of that year began ASTP (Army Specialized Training Program) at Auburn University, then known as the Alabama Polytechnic Institute.

At the end of March, 1944, the army closed down the ASTP programs throughout the country, and most of us at Auburn were shipped to Camp Atterbury, Indiana, where we joined the 106th Infantry Division and received training for combat during the following months. My 423rd Infantry Regiment was shipped to Europe aboard the Queen Elizabeth I, sailing from New York on October 17, 1944. We were housed in Britain for several weeks just outside Cheltenham, Gloucestershire, until shipped to France at the end of November. We arrived at the front, in the Siegfried Line just inside Germany, on Monday, December 11, 1944, five days before the Germans launched the Battle of the Bulge against us. Ordered to evacuate our position and go to a rendezvous point near Schonberg, Belgium, we reached our destination but were not “rescued” as planned. Our Regimental Commander surrendered the remnant of his regiment on Tuesday afternoon, December 19, 1944, to save us from death by German artillery fire.

Gifford Doxsee in his Army uniform

Processed as a POW by the Germans at Stalag IVB, Muhlberg, I was sent as part of an Arbeitskommando of 150 men to Dresden on January 12, 1945 where we were billeted in Building Number Five of the Dresden Slaughter-House Compound, later made famous by Kurt Vonnegut’s classic novel which was based on our common experiences. After the firebombing of Dresden, we were moved by our guards to the suburb of Gorbitz, and in mid-April, our guards marched us to the hamlet of Hellendorf on the Czech border, some 35 miles or so SE of Dresden. There we awaited the end of the war and the arrival of the Russians in whose zone of occupation we found ourselves. I returned to the U.S. Army control on Mother’s Day, May 13, 1945, and was given an honorable discharge from the army at Fort Bragg, NC, on November 25, 1945.

After the war I returned to college, graduated from Cornell in 1948, and then began graduate study in the history of modern Europe at Harvard. I received the M.A. degree in 1949 and the Ph.D. in 1966, having in the interim taught for three years at The American University of Beirut, Lebanon, 1952-1955, and subsequently at Ohio University, beginning in 1958.

I married Mary Letitia Cowan, a faculty colleague at Ohio U. on June 9, 1964, and we both continued our teaching careers at Ohio in the city of Athens. Mary had done a year of post-graduate study in textiles at Leeds University, Yorkshire, England, and her field of specialization thereafter was textiles in the Ohio University School of Home Economics. She retired officially in 1982 but continued teaching part time until 1989. I took early retirement in 1993 and retired fully one year later. The University honored Mary at her retirement by naming the assemblage of textiles and clothing the “Mary C. Doxsee Costume Collection.”

My service to Ohio University included chairing the Energy Conservation Committee in the 1970s and directing the graduate program in African Studies from 1983 to 1991. Our travels included numerous trips to Europe as well as professional travel to the Middle East and North Africa, the focus of my later teaching. Since retiring, I have served as adjutant/treasurer of the Mid-Ohio Valley Chapter, American Ex-Prisoners of War since 1996, as as JVC of the Department of Ohio since 1998.

Doxsee received the College of Arts & Sciences Outstanding Friend of the College Award in 1994. Doxsee pledged one of two gifts of $10,000 that launched the Appalachian Scholars Program at Ohio University.

Professor Emeritus of History Gifford Doxsee has pledged the initial gift of $10,000 for the Emeriti Appalachian Scholarship.

Parkersburg News and Sentinel reporter Jody Murphy captured the tale of Dr. Gifford Doxsee, a U.S. Army veteran and former Ohio University Professor of History. Doxsee spoke on Veterans Day at the Belpre Senior Center about his time as a POW in a German camp in the later days of World War II. “He was part of a large group of soldiers who surrendered to the Nazis after being surrounded during the Battle of the Bulge,” Murphy wrote.

Doxsee’s division was deployed to west Germany five days before the Nazis launched their offensive. After several days of fighting, Doxsee’s unit was surrounded by Germans.

The Nazi commander issued an ultimatum; surrender or die. Doxsee said his commander sacrificed his career instead of their lives and surrendered.

The POWs were taken to a camp near Dresden. Doxsee was held in Slaughterhouse Five alongside fellow soldier Kurt Vonnegut. Doxsee said Vonnegut, the tallest man in the group, served as an interpreter between the Americans and the Nazi captors.

Vonnegut would later write about the experiences of the POWs in his critically acclaimed novel Slaughterhouse Five.

Doxsee said as long as they obeyed the Nazi guards, they were treated well. The guards were older men in their 40, 50s and older who were too old to fight, Doxsee said.

“Our problem was lack of food,” he said.

The POWs spent several weeks in Dresden before moving to a village in the Czech Republic.

“We were woken up and told the Russians were coming from the east and the Allies were coming from the west,” he said. “They were worried we would be shelled.”

The POWs—already weak—marched 35 miles in two days to the village. Still, there was no food. Doxsee said they survived eating grass and dandelions. He lost about 50 pounds during his captivity.

Doxsee said the POWs retained hope throughout their imprisonment. A soldier made a short-wave radio out of a can and they were able to pick up BBC broadcasts to hear the progress of the war rather than rely on the lies of their Nazi captors.

“It kept our hope,” he said.

3 Comments