By Helen Cothrel ’15

Honors Tutorial College and Physics Major, Ohio University

Experimental physics has proven to be a fickle beast, but perseverance in the face of its vicissitudes is rewarding. In the lab this summer, first I had to master the tools, but then I learned the joy of experimentation.

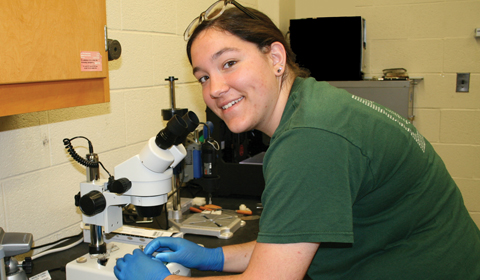

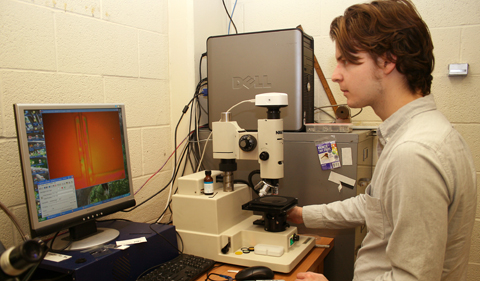

I have had the great fortune to spend my summer working in one of the Department of Physics and Astronomy’s physics labs under the direction of Dr. Eric Stinaff. My work has been made possible by an undergraduate research fellowship I received from the Condensed Matter and Surface Sciences Program at Ohio University. Throughout the course of my research, I have had the pleasure of growing acquainted with an excellent academic community, the trials and rewards of experimentalism, and the laser, an invaluable and versatile tool.

The bulk of my research has been focused on the sharpening of techniques for photolithography, which we will be using to attempt the fabrication of simple, micro-scale devices. Such devices could potentially be used to investigate the behavior of nano- and micro-scale materials such as quantum dots, or carbon nanotubes. My forays into photolithography have been made possible by the laser, for which I have nurtured a singular admiration. I have worked with lasers for not only photolithography, but also in a setup to measure photon entanglement that will hopefully be used in the undergraduate labs this fall—and my experience is notably limited compared to what I know awaits me. I realize now that the laser is extraordinarily versatile, but a tool’s versatility is dependent on its wielder, and versatility is learned only through practice.

Though physics-centered, my work also sampled chemistry and engineering, and I have seen that an appreciation for other scientific fields can be just as valuable as an appreciation for your own. The community of scientists with whom you have the potential to collaborate encompasses numerous fields, and recognizing the worth in the knowledge of others is an important step to becoming part of that community yourself.

My time in the lab has largely consisted of learning to problem-solve in many contexts. One of the most central—and capricious—of these has been the management of technology. The tools we use to explore physics are remarkable, and understanding their intricacies is an art of its own. The mastery of technology is honed over time, and it is made more useful if your flexibility grows as well.

When you’ve ironed out the frustrations in your equipment—which can be a result of a change to the tools, or the way you approach them—you begin the enriching practice of experimenting. The frustrations do not necessarily end, but they certainly become more enlightening. From every mistake or unexpected result comes valuable knowledge. Part of the satisfaction of this learning process is the ability to put new knowledge into practice immediately; as long as you never make the same mistake twice, you will always be learning.

As I once heard the physicist Michelangelo D’Agostino say, a physicist has the unique mindset of being able to learn anything he or she needs to learn to solve a problem. The more time I spend in physics, both in and out of the lab, the more I recognize the value of this mindset and the flexibility it bestows upon you. This approach to problem solving is learned well through physics, but its applications are boundless and diverse.

In retrospect, the wealth of knowledge that I have gleaned from this experience is both thrilling and humbling. I see in the laser an abundance of possibility, and that is what I find the most exciting. The abundance of support that I have received has pushed my understanding of both my subject and my community forward. I have been helped, pushed, prodded, and helped some more by both faculty and graduate students, and it is only with their help that I have been able to stand safely on the shore and dip but a toe into the sea of knowledge that churns before me.

Comments