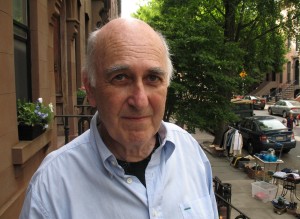

The 2016 Spring Literary Festival welcomes author Phillip Lopate for a lecture on Thursday, April 7, at noon, in Baker Ballroom, and for a reading at on Friday, April 8, at 7:30 p.m., in Baker Ballroom.

By Brad Modlin

Graduate student pursuing a Ph.D. in Poetry, with an emphasis on Creative Nonfiction

When describing Phillip Lopate, people use expressions such as, “the guru of the modern essay,” or, “the man whose name is virtually synonymous with the contemporary personal essay,” or—in the words of The Christian Science Monitor—“an essay authority who knows his territory down to his bones.”

Lopate directs literary nonfiction at Columbia University in New York and teaches in Bennington College’s low-residency MFA program. He has received a Guggenheim Fellowship, two National Endowment for the Arts grants, and two New York Foundation for the Arts grants. His more than twenty books include the essay collection Against Joie de Vivre; Notes on Sontag (about the life of Susan Sontag); Being with Children, which reflects on twelve years as writer-in-residence in a New York Elementary school; Waterfront (about the NYC waterfront); and the gold-standard anthology, The Art of the Personal Essay.

Maybe we can attribute his prolific publications to his belief that we are surrounded by writing material. As he once told Poets & Writers Magazine, “One of the ploys of the great personal essayists is to take a seemingly trivial or everyday subject and then bring interest to it.”

And so he does:

People talk in movie theaters, and in that, Lopate sees a growing cultural fear of solitude. Having a beard or not becomes a reflection of a man’s character and emotional state—“I grew the beard originally because I had been restless and dissatisfied with myself; I shaved it for the same reason.” Looking through a dresser drawer elicits not only memories over the knickknacks inside, but also a surprising guilt about the responsibility of caring for these objects indefinitely. Lopate’s work insists that a depth of meaning lies beneath our small tasks and decisions. When adopting a kitten, which to choose? If you pick the “straightforward” gray one, you value dependability. If you pick the milky-orange one, you value beauty more.

Apparently philosophizing about bringing interest to the everyday, Lopate writes in “The Moody Traveler,” “I was determined to slow down and practice ‘the discipline of seeing.’ It was a sometimes conviction of mine that, wherever one found oneself, the world was rich enough to yield enjoyment if one but paid close attention to details. Or, as John Cage once said, when something bores you, keep looking at it and after a while you will find it intriguing.”

But hold on. Let us note that Lopate says, “a sometimes conviction.” Let us note that he continues, “Inside, however, I rebelled against [Cage’s] notion…The day is boring…Let’s not pretend it’s any better.” And then: “I [sat] arguing these two positions.”

Herein is a second characteristic central to Lopate’s philosophy and work. He writes, “In the best nonfiction, it seems to me, you’re always made aware that you are being engaged with a supple mind at work.” He tells us that nonfiction’s storyline or plot “consists of the twists and turns of a thought process working itself out.” Lopate’s readers see a mind exploring the complexity of its own motivations. They see debates against oneself. Across a given essay, readers enjoy seeing questions answered, then re-asked, then answered again. Lopate chooses that gray kitten and a few days later realizes he didn’t want one at all. What he really wanted was to become the gentle old man who was giving the cats away. When the old man ends up giving him the orange kitten instead of the gray, Lopate is grateful because, after all, she was the symbol of beauty. (“Where do you begin your essays?” Harper’s Magazine asks. Lopate answers, “I often start out in a place that feels like a baffling cul-de-sac.”)

This love of the baffled/debating/working mind prompts Lopate to challenge a traditional dictum of writing, Show. Don’t tell. Hundreds of teachers have instructed their students: depict a situation, emotion, or thought, but don’t—heaven forbid!—talk about it directly. Au contraire, says Lopate, ever the fan of contrariety. In his recent book To Show and To Tell: The Craft of Literary Nonfiction, he encourages writers to both present a situation or experience and to directly comment on it. The essay, then, progresses along two tracks: the event and the reflection upon it. It the midst of a story about his failed first marriage, he says:

“I was twenty-two […] I mention my age partly to exonerate myself in advance for bad behavior. It was not that I behaved so despicably, which could at least allow me the retrospective allure of villainy, as that I was so passive and overwhelmed and inadequate to the challenge.”

His telling here adds to the piece’s universality. Telling allows the essay to be about not only the ineptitude of youth, but also about hindsight. The mind keeps changing.

His confession of somewhat “bad behavior” brings up a final, endearing trait of Lopate’s writing—his own human imperfection. To write a personal essay, he says in To Show and To Tell, a writer must notice his flaws. Readers will see themselves in those flaws, and they will become companions, even friends. Like we might do, he complains in beautiful Italy. Like most of us, despite a belief in honesty, he lies to escape awkward social situations: “I never called her back. I knew I wouldn’t even while I was making the offer[.]” And he admits, beyond what we might admit about ourselves, “I do not, by and large, perform good works[.]”

In The Art of the Personal Essay, Lopate tells us, “[T]o assert [the moralistic] may win a writer points in heaven, but it is doubtful that these pronouncements will quicken the reader’s pulse.”

Let’s be honest—people aren’t declared saints until after they are dead, their faults forgotten. Lopate encourages writers to present narrative selves who are very much alive. Opening up about weakness, paranoia, and discontent can be great fun. And those confessions resonate with readers who also happen to be imperfect and uncertain. In his poem (he writes those, too!) “We Who Are Your Closest Friends” he describes feelings we all may secretly share. Pay extra attention to the last two lines:

we who are

your closest friends

feel the time

has come to tell you

that every Thursday

we have been meeting

as a group

to devise ways

to keep you

in perpetual uncertainty

frustration

discontent and

torture

by neither loving you

as much as you want

nor cutting you adrift

[…]

we feel hopeful you

will continue to make

unreasonable

demands for affection

if not as a consequence

of your

disastrous personality

then for the good of the collective

The essayist uses his problematic self to benefit his audience, to bind people together, Lopate seems to say. It is this embracing of imperfection that enables Lopate 1) to find the interesting inside seemingly everyday details, and 2) to let readers see his working mind.

Nothing disastrous about that. In fact, we could call it a good work. A very good one.

Comments