The cemetery at Payne’s Crossing is the only visible remains of the once-vibrant community. Photo: Rich-Joseph Facun

All that’s left of Payne’s Crossing, an African American settlement dating back to the 1800s, is remnants of the cemetery?

Actually, there’s a lot more to discover about this once-thriving settlement founded by formerly enslaved people that likely served as a stop on the Underground Railroad. A team of Ohio University and University of Pennsylvania students and faculty just got a closer look, thanks to ground-penetrating radar and other non-invasive techniques.

They discovered there’s a lot more to learn about the community, whose land was purchased and mined by coal companies and is now buried beneath a hundred-plus years of soil and vegetation atop the Civil War era homesteads.

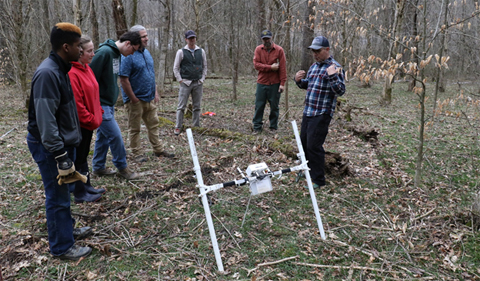

University of Pennsylvania Ph.D. Student Moriah McKenna, far right, trains Ohio University undergraduates, from left, Deontae Brown, Zach Lawson and Nellie Sullivan how to use a soil resistance meter to map underground features. Photo: Joseph Gingerich

In late March, a research team of archaeologists led by Cory Crawford (Ohio University), Joe Gingerich (Ohio University), and Andrew Tremayne (Wayne National Forest) collaborated with geophysical archaeologist Jason Herrmann (University of Pennsylvania) to use geophysical equipment to map historic settlements on the Wayne National Forest, where Payne’s Crossing is located.

Using non-invasive mapping techniques, the archaeologists surveyed both the locations of possible homes associated with the settlement and unmarked burials in the cemetery.

Students involved in the project conducted soil resistance surveys and used equipment such as ground penetrating radar to map obstructions or anomalies in the ground, such as foundations, grave shafts, and hearths. Herrmann’s team brought most of the equipment and included Ph.D. students from the University of Pennsylvania and the Center for the Analysis of Archaeological Materials at the Penn Museum.

From left, OHIO students Emma Kinsinger and Cassady Wallace collect ground-penetrating radar data at Payne’s Crossing Cemetery. Photo: Cory Crawford

Correcting the Description of Payne’s Crossing

“Most of today’s descriptions of Payne’s Crossing note that, besides the cemetery, nothing remains of the settlement. Archaeology is therefore the primary means of recovering and restoring the physical evidence of this important community, and I am grateful to Jason and his students for having come to share their resources and expertise with us,” said Crawford, Ph.D., associate professor of Classics and Religious Studies in the College of Arts & Sciences.

“It was a great opportunity to teach students cutting-edge survey techniques while investigating an important piece of Ohio’s history,” said Crawford, who organized and secured some of the funding for the project, which included financial support from the Central Region Humanities Center, the Classics and Religious Studies Department at OHIO, and the Center for the Analysis of Archaeological Materials at the University of Pennsylvania.

University of Pennsylvania archaeologist Jason Herrmann, far right, teaches the basic operations of a magnetic gradiometer. Photo: Joseph Gingerich

“I think what the most surprising and interesting thing that I learned while at Payne’s Crossing was probably the site itself. It is extraordinary that a predominately Black settlement like this was able to not only exist but thrive back in the 1850s,” said Deontae Brown, one of seven OHIO undergraduate students who took part in the March survey.

“I am so proud to be a part of a site like this and uncovering a history where African Americans were still able to make a name for themselves during a dark period of time. While at the site, I was also excited to learn about the various survey methods that archaeologists use before they even start excavating a site. I got to learn about things like the magnetometer, which was used to detect variations in Earth’s geomagnetic fields caused by buried metals and possible artifacts. This makes it easier to find the most optimal points for excavation,” said Brown, a senior majoring in Anthropology and Political Science Pre-Law and pursuing a Certificate in Law, Justice & Culture.

Next Steps for Researchers

Preliminary results of the non-invasive mapping have been promising, as they reveal likely features that might be explored in future excavations.

Crawford hopes to continue research at the site as it not only provides experiential learning opportunities for students but the possibility to work with many colleagues across the university and in the community. He noted that Gingerich and Tremayne connected him with this project because of his interests in the intersection of historical text and material culture discovered through archaeology. “Even though it lies outside my primary research focus in the Iron Age Eastern Mediterranean, this project seemed ideal to engage with given the renewal of the Central Region Humanities Center and the possibility to involve students from OHIO and Penn in the recovery of lost information about a crucial moment in Ohio’s history.”

“I am thrilled at the prospect of future collaboration with Ohio University on this project,” Herrmann said.

The team plans to discuss the work at OHIO at the fall conference of the Central Region Humanities Center and eventually to publish the results. With an emphasis on Southeast Ohio, the center is setting out to establish strong ties with academic programs, provide student experiential learning opportunities, support graduate and undergraduate students, and engage with community organizations.

Gingerich will have two interns working at the Wayne this summer and is collaborating with Tremayne, heritage program manager and archeologist at the Wayne and a research scholar in Anthropology at OHIO.

“We will probably devote some time to at least better establishing the site boundaries from the geophysical survey, and we will probably ground-truth some of the anomalies found with the equipment,” said Gingerich, Ph.D., associate professor of Anthropology in the College of Arts & Sciences.

Tremayne is also excited about the project, noting, “As heritage manager for the forest, my goal is to understand, protect and preserve sites. Knowing the boundaries and locations of previous settlements not only tells us more about the people that lived here but allows us to protect them and help tell their stories.” He hopes not only to nominate the site to the National Register of Historic Places but also to renew work with descendants and local community groups to highlight the rich history of the area.

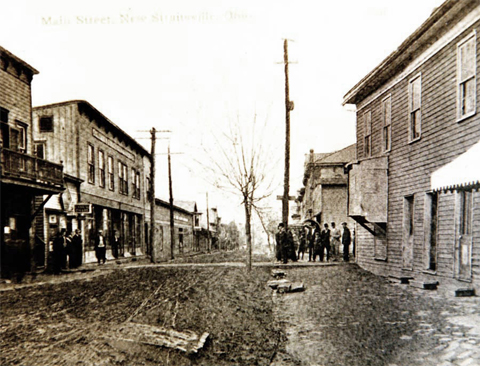

“The research on Payne’s Crossing will be important in a number of venues, in particular to regional history. The New Straitsville History Museum is looking forward to incorporating findings from this research into an exhibit for the town’s local history museum,” added Nancy Tatarek, Ph.D., associate professor of Anthropology at OHIO. She has worked on aspects of Payne’s Crossing for several years, and she and her students work with the New Straitsville History Museum.

About Payne’s Crossing

The OHIO-Penn research in March focused on Payne’s Crossing, an early settlement that was founded by formerly enslaved people in the 1830s. While settled originally by the Norman family, the Payne family, for which the area was named, bought property in the area in the late 1850s and moved there from Loudoun County, Virginia. Historical records show the cemetery associated with the settlement contains the remains of Civil War veterans who served in Ohio regiments of the U.S. Colored Troops.

The settlement has been referenced by various spellings over the years, including Payne’s, Paine, Paine’s, and Paynes.

The Ohio History Connection notes that “most early residents were freed or runaway slaves from the South, especially from Virginia. The community was never incorporated as a town. Rather, it was a small hamlet, consisting of several farmsteads. Many of the African-American residents established successful lives, accumulating sizable amounts of personal wealth…. By the twentieth century, no remnants of Payne’s Crossing survived except for the community cemetery.”

“By the 1850s, African American families owned most of the land,” and “farming and the iron industry dominated the landscape,” according to the Wayne website. “Research indicates that Paynes Crossing was a logical stop along the Underground Railroad and that the community’s residents were active in aiding freedom seekers. Today, only a cemetery remains as a physical clue about the stories of Paynes Crossing.”

OHIO researchers and students will be adding to this historical record as their work progresses.

See more of the Black history of the region in images by Rich-Joseph Facun.

Comments