Transnational Resonances: A mural on the Ciencias Sociales campus declares solidarity with the Palestinian liberation struggle.

On March 24, 1976, military leaders came for Argentine President Isabel Perón, ending her presidency not two years after her husband Juan Perón died in office. Argentinians would suffer more than seven years of persecution, including the murder and/or “disappearance” of approximately 30,000 people deemed “subversive” by the military dictatorship.

A new book by Loren Lybarger and two colleagues examines how remembering this tragic past can help people mobilize for justice in the present. He and a research team traveled to Buenos Aries in 2016 to analyze how the 1976 coup was commemorated 40 years later during events associated with Argentina’s national Day of Remembrance for Truth and Justice. (See a short documentary about their project.)

“These labors of justice manifest in three ways: as resistance, reconciliation, and recovery,” say Lybarger and co-authors James S. Damico and Edward Brudney in their book, “Commemorative Literacies and Labors of Justice: Resistance, Reconciliation, and Recovery in Buenos Aires and Beyond” (Routledge 2022).

The three scholars studied the literacy practices of commemoration—how individuals and groups make sense of the past through a variety of texts such as posters, exhibitions, rituals—drawing on research they conducted across three different sites in Buenos Aires in March 2016. The sites were a public university, a Catholic church, and a former naval base and clandestine detention center transformed into a museum space for memory and justice.

“We chose those three locations very intentionally because of the roles played by these institutions during the coup and the years of repression that followed,” said Lybarger, professor of Classics & Religious Studies in the College of Arts & Sciences at Ohio University. “While the military was in power, the Catholic Church in Argentina also was entwined in what became known as a defense of ultra-conservatism, but that wasn’t the only role it played since other Catholic leaders and communities actively resisted the regime. We focused, for example, on a church that had become a target of the regime violence and now serves as an important site of remembrance of the disappeared.”

A similar rationale led the authors to university sites in Buenos Aires that were part of the military regime’s efforts to disappear scholars, educators, and students deemed “subversive.”

Damico, professor of Literacy, Culture, and Language Education at Indiana University noted, “Our time at these university sites shed a great deal of light on the ways commemorative literacies mobilized memory of the past for very particular present-day political purposes related to resisting current policy proposals of the existing government.”

A former naval base, the ex-ESMA, which now functions as a dedicated “memory space,” provides the book’s third case study. “The ex-ESMA has become synonymous with the dictatorship’s use of extralegal violence, given its status as the regime’s largest clandestine detention center,” explains Brudney, assistant professor of History at the University of Tennessee at Chattanooga. Over the past 20 years, debates about what to do with the physical space have brought questions about public commemoration to the fore, making it a uniquely appropriate site to consider how Argentine society remembers and copes with the legacies of violence handed down from the 1970s.

“What we found sheds light on the ways commemorative literacies at these locations work spatially to draw on the past to address and advance justice concerns today,” Lybarger said. “Three themes of justice emerged, including continued resistance against efforts to subvert democracy and human rights, reconciliation only after a full and honest accounting for the past, and recovery of memory both as an archival project and as a personal, familial and artistic effort to retrieve memories of the disappeared.”

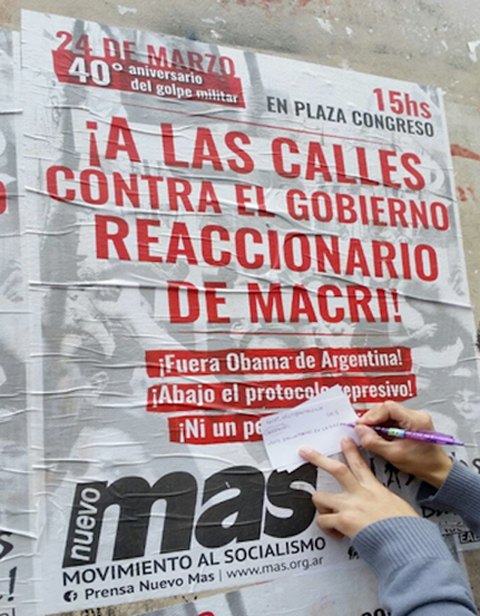

A poster visible on the Ciencias Sociales campus of the University of Buenos Aires during the 40th Anniversary Commemoration of the Period of State Terror refers to the commemoration and calls on Porteños (residents of Buenos Aires) to take to the streets to protest the “reactionary” policies of the Macri government in power in 2016, when this photo was taken. It also demands that U.S. President Obama leave Argentina. The former president had planned to attend the 40th anniversary events.

Through their work, Damico, Lybarger, and Brudney also demonstrate how commemorative literacies like those in Argentina resonate not just within a single country, but also within a world looking not to repeat the mistakes of history.

“In our final chapter we draw connections with justice struggles elsewhere such as civil rights and Black Lives Matter in the United States or the Arab Spring and the Palestinian struggle,” Lybarger noted. These transnational links appeared in posters and murals in Buenos Aires. Damico recalled seeing “images of Dr. King at the Church of Santa Cruz, one of our research sites—so, one of our key discoveries had to do with how the Argentine experience leads to this transnational perspective and sense of a global response and responsibility for justice struggles in diverse spaces.”

Transnational and transhistorical connections: Images in the style of orthodox iconography depicting St. Joan of Arc, St. John of the Cross, the Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. of the United States, and Archbishop Oscar Romero of El Salvador. These images appeared at the Church of Santa Cruz in Buenos Aires.

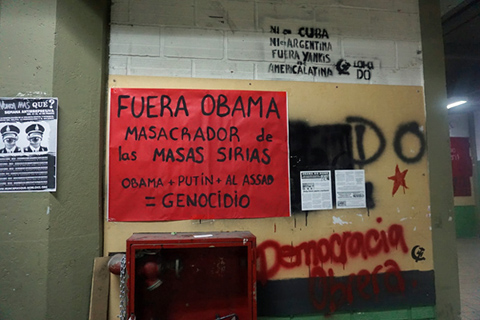

Transnational Resonances: Posters and stenciling at the University of Buenos Aires mark the 40th Anniversary of the Period of State Terror and draw links to state-sponsored repression and abuse in other places like Syria.

For Lybarger, the connection between religion, the Argentine experience, and its global resonance is especially crucial to examine. “As a religious studies scholar, it’s important to look at intersections where religion, state violence and political identity come together and to conduct ethnographic studies in the field,” said Lybarger, who has written extensively about Palestinian experiences in the West Bank and Gaza Strip and in Chicago. He and Damico are also developing a new project focusing on how religion shapes responses to climate disaster.

Comments