“The settling of Ohio is all about the rivers—what the settlers called the Western waters,” said Dr. Kim Gruenwald at the Settling Ohio: First Nations and Beyond conference held Feb. 21-22 at Ohio University.

She went on to describe trade bounded by the movement of goods when river conditions were right—enough water flowing to move goods from the headlands in northeastern Ohio, but avoiding the ice flows of winter.

After the American Revolution, the Ohio River served as the main thoroughfare for the Western Country as merchants created a river-based economy with ties across along western rivers on both sides of the Ohio and between West and East, helping the new United States claim the trans-Appalachian West for its own.

The two-day conference organized by Dr. Brian Schoen, Associate Professor of History at Ohio University, and Dr. Tim Anderson, Associate Professor of Geography, looked at the many ways Ohio was shaped by its first settlers, including how they built the state’s government, economy, agriculture and homes.

At the conference opening, Schoen noted that no one knew in 1760 who would ultimately control the region between the Ohio River and Great Lakes, one of the most fertile and resource rich regions in the world. Several speakers touched upon the dynamics of power and the chaotic, often violent processes that determined and evidenced that outcome.

Dr. Cameron Shriver of the Myaami Center at Miami University discussed how knowledge guided power as British, French, and various Indigenous peoples fought to control land and information during the French and Indian War (1754-1763).

Temple University’s Dr. Jessica Roney showed how the pattern of state creation set up by the Northwest Ordinance was not the bottom-up story often told, but rather one in which the United States congress ultimately determined who deserved self-government.

Joseph Ross, an alum of Ohio University’s history graduate program, discussed how, contrary to the image we usually have, Federalist power created chaos in the Northwest Territory by the haphazard granting of private land and wars with native peoples.

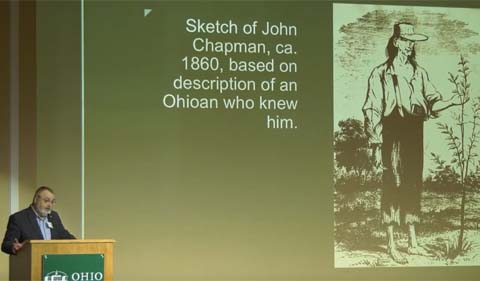

Johnny Appleseed and the Truth about Apples

The Ohio River especially dictated the fortunes or misfortunes of the early settlers into the Northwest Territory. Dr. William Kerrigan talked about the early settlers in Marietta bringing with them apple tree grafts to start orchards bearing fruit that would survive the tedious journey down the Ohio River, to the Mississippi River, and eventually to the trade center of New Orleans.

He described apples as a symbol of “class, wealth and power.”

He provided a fact check on David McCullough’s book The Pioneers, noting that apple seeds—those carried by Johhny “Appleseed” Chapman and those in all apples today—produce wild apple trees bearing often gnarly or bitter fruit. Apple varieties are produce by grafting, not by planting seeds.

And he used this difference to illustrate another dichotomy between the prominent, moneyed early settlers whose names star in McCoullough’s book and on signposts around Southeastern Ohio. They had the means to transport young trees and grafts, whereas Johnny Appleseed saw value in the wild apples for subsistence farmers. Wild apples could provide food for their families and their livestock as well as cider and vinegar.

Kerrigan also gave a nod to the late Dr. Hubert Wilhelm, a geography professor whose work on Ohio settlements is still a key source for researchers today.

Walking Ohio’s First Road

Among the historians and geographers sharing their research and telling tales of the Northwest Territories was Ohio University alumnus William Hunter, Cultural Resource Manager and Outdoor Recreation Planner, National Park Service, Cuyahoga Valley National Park.

Hunter told of setting out to walk Zane’s Trace, the first official “road” in Ohio, connecting Wheeling, W.V., to what is now Maysville, Ky., for his master’s thesis in geography.

Zane’s trace was designed to save time and money by moving goods and people quickly to the Ohio River. It was made obsolete by more modern roads, railroads and even canals.

Even in its heyday the trace was nothing like the roads of today. In parts it wasn’t even a very worn path. It was more like a directional guide from one tavern to the next. About every three miles Hunter would discover a tavern or a tavern site that served as food and shelter for travelers and commerce of the past.

Word soon spread of his journey, Hunter says, with residents and even a professor and students eager to greet him and share their stories as he made his way down the trace.

Zane’s Trace, was the first formally sanctioned nonmilitary road in the Northwest Territory, along ancient trade routes by a party led by Virginian Ebenezer Zane in 1796-1797. Extending along the southern extent of glaciation, the trace ran across different landforms and land survey systems, linking the Mid-Atlantic to the South via a series of inland river towns, producing a complex linear cultural landscape. It was made remote by the shifting scales of transportation, political machinations and westward settlement. Yet the current fragmentary landscape demonstrates not only the persistence of Zane’s Trace through time, but also points to powerful historical processes that engendered its development, disillusion, commemoration and designation. The many representations of the trace express the differential processes of landscape change that typify the variegated land use of the edge of Appalachian Ohio.

Comments