Ohio celebrates Statehood Day on Feb. 26, 2020, with one contentious issue still lingering since the founding of the state—property tax funding of public education.

Two speakers at the Settling Ohio conference, held at Ohio University Feb. 21-22, 2020, talked about how taxpayer funding of public education, while deemed to be a public benefit, proved difficult to implement. Conflict arose early in Ohio, especially in the 1800s when African American property owners were taxed but did not have access to schools.

Using property taxes to pay for schools remains an unresolved issue today, despite an Ohio Supreme Court ruling in 1997 ordering “a complete systematic overhaul” of Ohio’s property-tax funded school system, writes OHIO’s Dr. Thomas Suddes in a Feb. 23 column in the Columbus Dispatch headlined “Fixing school funding mess, and vouchers, shouldn’t be so hard.”

“Exactly 8,371 days ago today, the state Supreme Court ordered ‘a complete systematic overhaul’ of how Ohio — unconstitutionally, the justices ruled — funds public schools,” he wrote. “That was in 1997. In the 23 years since the court decided what’s called the DeRolph case, Ohio’s had six governors. Ohio’s House has had seven speakers. Ohio’s Senate has had six presidents. And Supreme Court Justice Francis E. Sweeney Sr., the Lakewood Democrat who wrote the court’s DeRolph decision, died in 2011. Yet — essentially — nothing has changed.”

An Early Commitment to Education Didn’t Translate into School Access

Ohio University students walk past the Alumni Class Gateway each day, though they might not read the inscribed passage from the Northwest Territorial Ordinance of 1787: “Religion, morality, and knowledge being necessary to good government and the happiness of mankind, schools and the means of education shall forever be encouraged.”

Dr. Anna-Lisa Cox noted that the founding document of the Northwest Territory mentioned neither race nor the exclusion of any group when it came to education or voting rights. But by the time the Ohio constitution was written, race was at the forefront.

Cox started her talk with a story about a young white schoolteacher and a community of African-American landowners and farmers. In her research she has mapped more than 300 settlements of propertied, prosperous African American farming communities in the Northwest Territories.

- Watch Dr. Anna-Lisa Cox’s talk on YouTube: “What if Manasseh Cutler was Black? The Hidden History of the Diverse Pioneers Who Created Ohio”

The Tale of Clarissa Wright

“It starts in 1839, which is fairly late in Ohio’s settlement, but this is an important chapter in Ohio’s past that reveals much,” began Cox, a non-resident fellow at the Hutchens Center, Harvard University. “So it’s Portage County, Ohio, in the deep countryside roughly 30 miles south of Cleveland. There had long been settled and successful African American farmers in that county. And by 1839 they organized and financed a lovely grammar school for their youngest children—because the white county leaders refused to build them a school with the tax money they had taken from those black propertied farmers.”

Wright was “a white woman willing to come on her own to live with these farmers and teach their children. Clarissa Wright knew exactly what she was getting into,” Cox said, describing her anti-slavery father who founded a school in Portage County called the Talmadge Academy to teach both boys and girls, among them abolitionist John Brown.

“In those days teachers usually boarded with a family involved in the management of the school. In this case, it would have been an African American family…. There should have been nothing upsetting about this. Education was supposed to be a core value in Ohio, a central pillar of a healthy democracy,” Cox said. But “the idea that a white woman would not only be equal to but dependent on wealthy African American farmers for her livelihood was not to be tolerated…. It was a killing offense.”

Threats ensued. Including plans to tar and feather Wright.

“Clarissa Wright seems to have escaped alive, but there is little record of what happened to school or the children she was trying to teach, and this event sums up in so many ways the complicated history of race relations in antebellum Ohio. Whites fighting with whites over questions of equal rights. African Americans aligning themselves with supportive whites, even as other whites tried to destroy them.”

The Challenges of Funding Early Public Education

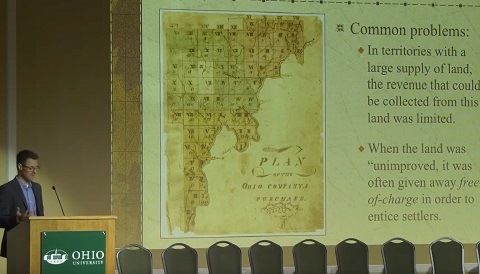

Dr. Adam Nelson, the Vilas Distinguished Achievement Professor of Educational Policy Studies and History at the University of Wisconsin-Madison, gave a keynote on “Public Education in the Old Northwest: Legacies of Ohio’s First Land Grant.”

He considered the “challenges that people like Manasseh Cutler and his son, Ephraim Cutler, faced in their effort to establish public schools on the settlers…. The idea that republican government hinged on schools funded by taxation was hardly new. Thomas Jefferson had made this case as early as 1779 in his famous Bill for the More General Diffusion of Knowledge, which assumed that voters would accept property taxes for public schools as soon as they understood how education helped every citizen.”

The Northwest Ordinance attempted to set aside revenue from the sale of federally owned lands to education. “Specifically, 1/36 of the land in each six-square-mile township was to be rented or sold, with the proceeds used to pay for a public school building and teacher.”

In short, “How could states offer public education if no one wanted to pay for it?” Nelson asked. “Particularly in a border region increasingly divided over the issue of slavery and by the late 1820s and early 1830s and the abolitionist movement as it picks up in the 1830s, it was not clear that public schools and colleges would be able to satisfy a polarized electorate. So contentious was the debate that even Horace Mann himself in Massachusetts refused to support racially integrated public schools.”

The two-day conference organized by Dr. Brian Schoen, Associate Professor of History at Ohio University, and Dr. Tim Anderson, Associate Professor of Geography, looked at the many ways Ohio was shaped by its first settlers, including how they built the state’s government, economy, agriculture and homes.

Not an Easy Path for OHIO’s Board

Dr. Ann Fidler, former history professor, dean and administrator at Ohio University, discussed the early days of the university’s board of trustees in “‘Warm Friends and Suitable Characters’: The Early Days of Governance at Ohio University.”

From the earliest days of his involvement with the enterprise that became the Ohio Company of Associates, Manasseh Cutler envisioned a set of communities arrayed around a university. He lobbied hard for the university’s establishment, wrote eloquently of its purpose, and drafted the charter that was to guide its governance. However, as Cutler chose to remain in Massachusetts, the actual development and administration of the university fell to residents of the Ohio Country. The history of governance at Ohio University highlights the complex personal, political, and cultural interactions that influenced both local and regional developments in higher education during the early national period.

Comments