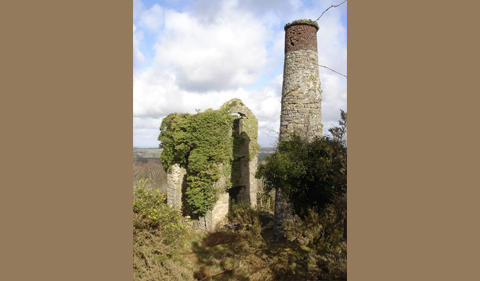

The houses of Holman’s 70-inch (foreground) and Rule’s 40-inch pumping engines, the boiler house of the larger engine and the stump of the stack (left) that served both, and the loadings and separate stack (background) of Rule’s 24-inch horizontal whim at South Caradon Mine (2014).

A new book by Dr. Damian Nance, “A Complete Guide to the Engine Houses of Mid-Cornwall,” documents the history of an unlikely UNESCO World Heritage Site in the U.K., the Cornwall and West Devon Mining Landscape.

Nance is Distinguished Professor Emeritus of Geological Sciences at Ohio University.

Visitors to the tiny county of Cornwall in Southwest England might be surprised to learn that, in 2006, the county’s landscape was judged to be of such importance that it was elevated to World Heritage status, on a par with Stonehenge and the Acropolis. But this was not because of its picturesque beauty, which is obvious to all, but because the landscape preserves evidence of the county’s pivotal role in the history of metal mining.

Nance was born in Cornwall and, in his youth, became fascinated by its old mines, and a parallel interest in photography led to the creation of a photographic record of the mining ruins that dotted the landscape 50 years ago. These now-important images harken back to a time when Cornwall was the “silicon valley” of the mining industry, providing the world with untold mineral riches and exporting its mining expertise and technology around the globe.

House of the 26-inch winding engine at Marke Valley Mine. Built by William West’s St. Blazey Foundry in 1876 and acquired from nearby East Phoenix Mine, it erected midway between Salisbury and New shafts so that it could hoist from both. It was offered for sale when the mine closed in 1890 (2012).

Cornwall is one of the most richly mineralized areas in the world, and the importance of its mineral wealth has been recognized since the time of the Ancient Greeks who traded with the Cassiterides (“tin islands”) as early as the 5th century BC. During the Middle Ages, the industry was considered to be of such importance that its miners were granted special privileges and placed under the separate legal jurisdiction of the tannary (“tin mining”) courts.

However, it was not until the Industrial Revolution of the 18th and 19th centuries that the full measure of this remarkable resource was exploited. During peak production in the mid-19th century, Cornwall and neighboring West Devon produced almost half of the world’s supply of copper and over half of the world’s supply of tin and arsenic. In addition, the county produced substantial quantities of lead, silver and tungsten, and significant amounts of zinc, iron, uranium, nickel, cobalt, manganese and bismuth.

View of the 30-inch rotative engine house at East Caudledown clay pit (left) and the 25-inch pumping Engine (9 ft equal beam) at Cleaves clay pit (right). The circuitous history of the latter is illustrative of many engines. It was built around 1864 by Thomas and Co. of Charlestown for nearby Appletree Mine but was never erected and went, instead, to Kerrow Moor Mine, near Rosevear, in about 1874. From there it went to Toldish Mine, near Fraddon, in or shortly before 1887 and finally to Cleaves China Clay Works soon after 1900. Both engine houses were lost to expansion of the Goonbarrow china clay pit around 1970. (August 1965).

What made the unparalleled productivity of the 19th century possible was the harbinger of the Industrial Revolution itself, namely the invention of a reciprocating steam engine, or beam engine, capable of driving pumps that could keep the ever-deepening mines free of water, hoist the mineralized ore out of the mine, and work the machinery needed to process the raw mineral. Because they needed to withstand considerable operational stresses, the buildings used to house these massive steam engines were heavily built, as a result of which many have survived the century or more of neglect since the engines they contained were removed, and today stand as silent monuments to the mining industry for which the region was once justly famous.

Indeed, nothing has come to symbolize the county’s rich mining heritage more than the castle-like engine houses that form such prominent and characteristic features of the Cornish landscape.

Nance’s new book, “A Complete Guide to the Engine Houses of Mid-Cornwall,” is the second of a trilogy of guides that describe the surviving engine houses of Cornwall. The guides are illustrated with both contemporary and archival photographs. They outline the histories of the mines they represent and summarize what is known of the steam engines they once contained.

Like its predecessor “A Complete Guide to the Engine Houses of West Cornwall,” the book is not meant solely for the enthusiast, nor is it an exhaustive treatment. Instead, it is an overview intended for all those interested in Cornwall’s remarkable mining heritage. The new book, published by Lightmoor Press in the U.K., is co-authored with the late Kenneth Brown, a leading expert on Cornish mining history, and Tony Clarke, an authority on Cornish mineral processing.

House of the 100-inch (11ft by 9 ft stroke) pumping engine at East Wheal Rose, near Newlyn East. Built in 1853 by Harvey and Co. for Great Wheal Vor, the engine was sold to the Great Hendre lead mine near Mold in Flintshire in 1865, where it worked until 1868. Repurchased by Harveys for East Wheal Rose in 1881, it was fitted with a shorter bob and re-erected beside North Wheal Rose shaft by Matthew Loam, son of the original designer. Here it worked from 1884 until the mine’s closure in 1886. Re-bought by Harveys, it was sold to the Whicham Mining Co. in Cumbria, in 1888 (2013).

Comments