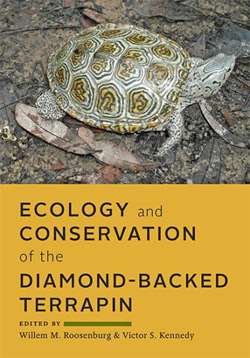

Roosenburg Co-Edits ‘Ecology and Conservation of the Diamond-Backed Terrapin’

By Kelly Shockley ’19

Dr. Willem Roosenburg, Professor of Biological Sciences co-edited and co-authored several chapters in a recently published book titled Ecology and Conservation of the Diamond-Backed Terrapin (Johns Hopkins University Press).

His co-editor was Victor S. Kennedy. In 19 well-written chapters, the book details current understanding of terrapin biology, physiology, behavior, and conservation efforts.

His co-editor was Victor S. Kennedy. In 19 well-written chapters, the book details current understanding of terrapin biology, physiology, behavior, and conservation efforts.

Roosenburg started working on the conservation and ecology of terrapin turtles in 1984. The book also details much of the terrapin conservation work that Roosenburg has accomplished on a portion of Poplar Island in Chesapeake Bay since 2012. Poplar Island is an island restoration project managed by the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers and provides a unique living laboratory to study the reintroduction and ecology of the terrapins. Roosenburg is also Director of the Ohio Center for Ecology and Evolutionary Studies.

Fighting Fisheries, Engineering Crab Pot Solution

As a lover of biology, Roosenburg was fascinated by nature from a young age. In his sophomore year of college at the University of Rhode Island, he met an adviser who helped to reinstill the inspiration that he obtained as a child. He then went on to do work in Costa Rica for three years and helped to run a sea turtle nesting station. Upon completing this work, he came to Ohio University where he was inspired to continue to work with terrapin turtles.

Dr. Roosenburg is flanked by Biological Sciences students that work with him studying the Terrapins in Chesapeake Bay during the summer months.

When describing the background of the terrapin, Rooseburg notes, “It has a very unique history with regard to most species of turtles in that in the late 19th to early 20th century it was considered a culinary delicacy. One of the consequences of this was that most of the populations within its range became pretty much decimated.”

When he started working on terrapins in 1987, there were several hundred found in a day. This gave him cause to work on his study further. In the early 2000s, the export of turtles from the United States to markets in the far east started putting new pressures on many new species of turtles, including the terrapin. Roosenburg, along with others, established an initiative to protect the species. He works to conserve these turtles to the best of his ability at multiple field sites, including the one he owns in Maryland.

“To this day, we have managed to close the fishery on terrapins in every state except for Louisiana,” he notes.

However, there is still a lot of work to do in order to revive the species. Roosenburg works rigorously to minimize harm on the terrapins.

“Probably the biggest challenge for the species is that they also get caught as bycatch in commercial fishing gears,” he notes. When Terrapins get caught in crab pots, which are used to catch the popular blue crabs on the East Coast, they drown. “We are fairly confident that the leading source of mortality for turtles currently is getting caught in the crab pots.” Roosenburg’s work includes designing and testing a “bycatch reduction device,” shown below, which prevents turtles from getting into the crab pots.

As one of the first researchers to rigorously test the device, he was able to demonstrate that if you put it in your crab pots, you can reduce the catch of turtles by 80 percent.

“My final goal is that we end up with a federal regulation that requires the use of these in crab pots…. In my opinion, crab pots are the number one threat to the species at this point,” he says.

Roosenburg plans to continue his work with fellow researchers and students at Ohio University.

Comments