You may be more familiar with the name of Barilla from the pasta aisle of your local supermarket. The company, founded in 1877 as a bakery shop in Parma, Italy, by Pietro Barilla, has grown to a multi-national corporation with an annual revenue of more than $450 billion (2015).

In 2004, Barilla opened the Academia Barilla in Parma, dedicated to the diffusion, promotion, and development of Italian gastronomic culture.

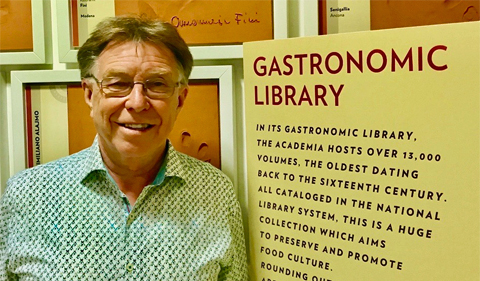

Part of the Academia is the Barilla Gastronomic Library, which houses more than 13,000 titles, some dating back to the 16th century, with specific sections dedicated to culinary history and culture; important gastronomic events; classic cookbooks; diet and nutrition; ingredients and how to use them; and regional Italian, and international, cuisines.

But what brought Dr. David Bell, Associate Professor & Chair of Linguistics, and Dr. Theresa Moran, Director of the Food Studies theme, was the collection of 5,000 historical menus from the 19th and 20th centuries.

Bell and Moran were particularly interested in the menus from the state banquets of Vittorio Emanuele III (1900-1946). With the unification of Italy in 1861, the House of Savoy, the Alpine region between what is now France and Italy that had previously ruled the Kingdom of Sardinia, assumed the monarchy of the new Italian state. Menus from the reign of Vittorio Emanuele III not only tell the story of the development of a national Italian cuisine – up until 1908 French was the language of Italian state menus – but also reveal how choices of dishes, ingredients, cooking styles, sequences of courses, and their linguistic expression reflect larger political forces.

In the period of il ventennio fascista, 1922-1943 and the overthrow of Mussolini and the Italian Government surrender to the Allies, fascist food policies reversed important trends in food culture and nutritional levels by embracing the notion of alimentary sovereignty, or total self-sufficiency with regard to food supplies. The fascist regime reduced food imports while encouraging the consumption of an austere diet based on bread, polenta, pasta, fresh produce and wine.

By comparing menus from state banquets from the first half of Vittorio Emanuele III’s reign with the fascist period, Bell and Moran want to know if royal and diplomatic receptions reflected fascist food policies both internally to Italian elites and externally to the international community.

Bell and Moran will present the findings of their research at the Kings and Queens Conference 8, organized by the Royal Studies Network in conjunction with the Royal Studies Journal at the University of Catania, Italy, June 24, 2019.

Comments