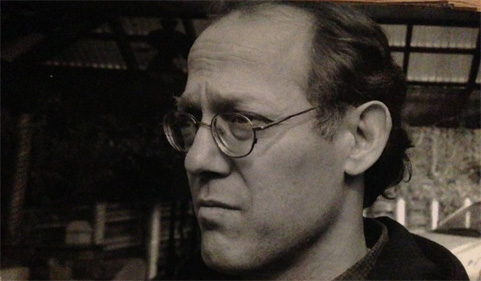

The 2018 Spring Literary Festival welcomes author Alan Shapiro for a reading on Wednesday, April 11, at 8:30 p.m., and for a lecture on Thursday, April 12, at noon. Both events will be held in Walter Hall Rotunda.

By Derek J. G. Williams

Graduate student pursuing a Ph.D. in Creative Writing: Poetry

“I can’t embrace the belief that art redeems our losses, nor can I afford to live without it.”

– Alan Shapiro, the Atlantic

I first encountered Alan Shapiro at an Association of Writers & Writing Programs panel entitled “The Art of the Joke.” I had never attended a conference before, never mind one so large and overwhelming. I had no idea what to expect, but for an hour and a half, Shapiro and three colleagues shared anecdotes and dirty jokes. They cracked each other up. They seemed to be having a great time up there, at the front of a huge ballroom in a well-appointed Chicago hotel. Their enjoyment of the conversation helped me enjoy and appreciate it that much more. My favorite joke of the session ended with the punchline: “Did I shit?” Following the talk, which I considered to be a wonderful performance, I listened to several of my fellow audience members complain. I could not quite put my finger on why they were complaining. I guess they were expecting a dissection of the joke and the role of humor in contemporary literature. Thankfully, on that cold Chicago day, that is not what they got. Not at all. Not even a little. Shapiro’s poems, much like that Chicago panel, are smart and funny without ever being overly formal.

Alan Shapiro has published over ten books of poems and several collections of essays. He is an expert in the volta—the poet’s punchline—and his punchlines defy traditional literary expectations. His poems reveal and revere our basest, most vulnerable selves, dispelling any romantic notions we might harbor about ourselves. They elucidate the joys and foibles of having a body—dancing and dying and drinking and living—and, yeah, the poems are frequently funny, too. His poem “To the Body” examines our vexed state:

clay dreaming spirit dreaming clay

at one

and the same

time pleasure dome

and torture chamber,

prisoner and

cell and cell

wall through which

the prisoner taps out

a message . . . .

His speakers are eager to connect, and glad to be alive, though they acknowledge the difficulty of that simple feat.

Shapiro writes with an unflattering sincerity. In a 2002 interview with The Atlantic, he addressed his approach to writing, what it can and cannot do for us:

The art I’m most interested in is the kind that cultivates compassion and sympathy and broadens our imaginative as well as intellectual horizons. But at the same time, it doesn’t insulate you from anything. It doesn’t provide you with equipment for the worst things that could happen. We are ultimately needy and vulnerable creatures, and there’s nothing we can do to make us any less needy and vulnerable.

According to Shapiro, poetry is not a balm to ease the pain of a burn or wound. If anything, poetry brings us closer to the worst things that can (and often do) happen. Poetry cannot help us, but it helps articulate our needs. At its best, it gives us another chance to understand each other a little bit better, a little bit more.

Alan Shapiro’s work has been helping us understand each other for over thirty years now, and he has been recognized along the way. He was a finalist for the Pulitzer Prize in 2012 and the National Book Award in 2008, and he is currently the William R. Kenan Jr. Distinguished Professor of English and Creative Writing at the University of North Carolina.

While the poet Emilia Phillips has said that his writing “seem[s] driven less by . . . idea[s] than an empathetic and playful heart,” it’s Shapiro’s antic sincerity that drew me to his voice at that panel so many years ago; it’s what brings me back to his poems now. Given his longevity and the magnitude of his accomplishments, I’m certainly not alone in this feeling. Readers and critics have appreciated his writing since before I was even born.

In the title poem of his new collection, Life Pig, an “oddly delicate” pig digs and feeds “till at last the head lifts up / defiant nostrils pulsing wide / as if to suck in the even bigger pig of the sun / which as it eats is glistening.” The pig’s relentless hunger is life-affirming. Its need is tremendous, disgusting, and greedy, mimicking our needs, our hunger and will to keep living. The poem punctuates a number of the conflicts inherent in so much of Shapiro’s work. We want so much more than we can have. Life demands and takes what it wants. All that is left to consider is what we are left with.

These ideas become clearer near the end of the book in the poem “Enough.” It is framed as a prayer to the God, “whom I don’t even think exists.” The speaker asks and even begs for the death of a loved one who is suffering. In this case, the poem refers to the figure of the mother who has been brought to life throughout the collection. The tone shifts from anger—“knock it off, / you sick fuck / this isn’t funny anymore”—to weary resignation by the time we reach the poem’s conclusion:

endless fooler, inexhaustible,

insatiable . . .

you’re never done

with us, or her, not

even now when there is

hardly anybody there

to get the joke.

The joke is a cruel one. While we might pray for someone we love to live, this poem pleads for her death. For the mother to continue on in a diminished state is an affront to the kind of vivid, dynamic life Shapiro imagines, and the speaker’s prayer for death is in fact empathetic, merciful.

It’s a death that helps us, forcing us to confront life’s limits. In art, the evocation of death creates an opportunity of us to resituate ourselves in the world. That may be scary, but it’s useful, and Alan Shapiro’s writing is fearless in this pursuit. He doesn’t shy away from ugliness.

In an interview published in 32 Poems, he spoke to just this point, saying “Each poem (ideally) is like a line in the poem of a life . . . I’d like to think of poems opening out to other poems rather than closing down or ending . . . finality gives me the creeps . . . I want [it] said at my funeral: ‘Look! He’s moving!’”

Is death, then, the ultimate joke? Merciful. Funny. Sad. Ridiculous. I suppose it depends on whether you are the one still living or not. Thankfully, we have Alan Shapiro’s writing as a reference point. It is, at the time of this writing, very much still moving.

Comments