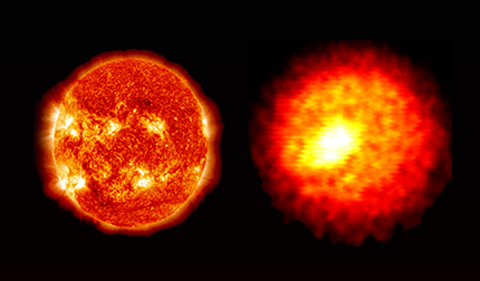

Despite staggering differences in mass and scale — the sun (left) is approximately 10^38 times more massive and 10^13 times larger — NIF implosions (right) are being used to recreate the conditions found in the deep interiors of stars so that they may be better understood.

“Stars are giant thermonuclear plasma furnaces that slowly fuse the lighter elements in the universe into heavier elements, releasing energy, and generating the pressure required to prevent collapse. To understand stars, we must rely on nuclear reaction rate data obtained, up to now, under conditions very different from those of stellar cores,” say researchers in a Nature Physics article.

“Most of the nuclear reactions that drive the nucleosynthesis of the elements in our universe occur in very extreme stellar plasma conditions. This intense environment found in the deep interiors of stars has made it nearly impossible for scientists to perform nuclear measurements in these conditions — until now,” writes Breanna Bishop of Lawrence Livermore National Laboratories.

Bishops’ story, “Scientists probe the conditions of stellar interiors to measure nuclear reactions,” reports on an article published June 29 in a Nature Physics journal titled “Thermonuclear reactions probed at stellar-core conditions with laser-based inertial-confinement fusion.” Dr. Carl Brune, Professor of Physics & Astronomy at Ohio University, is a co-author on the paper.

“It was a exciting to work with the team from LLNL, MIT, and LANL, which included alum Daniel Sayre (Ohio University Ph.D. 2011) from LLNL who I supervised as a graduate student. This research paves the way for further studies of reactions that may occur inside of stars using thermonuclear plasmas at the National Ignition Facility,” Brune says.

In a unique cross-disciplinary collaboration between the fields of plasma physics, nuclear astrophysics and laser fusion, a team of researchers, including scientists from Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory, Ohio University, the Massachusetts Institute of Technology and Los Alamos National Laboratory, describe experiments performed in conditions like those of stellar interiors. The team’s findings were published today by Nature Physics.

The experiments are the first thermonuclear measurements of nuclear reaction cross-sections — a quantity that describes the probability that reactants will undergo a fusion reaction — in high-energy-density plasma conditions that are equivalent to the burning cores of giant stars, i.e., 10-40 times more massive than the sun. These extreme plasma conditions boast hydrogen-isotope densities compressed by a factor of a thousand to near that of solid lead and temperatures heated to approximately 50 million Kelvin. These are the conditions in stars that lead to supernovae, the most massive explosions in the universe.

“Ordinarily, these kinds of nuclear astrophysics experiments are performed on accelerator experiments in the laboratory, which become particularly challenging at the low energies often relevant for nucleosynthesis,” said LLNL physicist Dan Casey, the lead author on the paper. “As the reaction cross-sections fall rapidly with decreasing reactant energy, bound electron screening corrections become significant, and terrestrial and cosmic background sources become a major experimental challenge.”

The work was conducted at LLNL’s National Ignition Facility (NIF), the only experimental tool in the world capable of creating temperatures and pressures like those found in the cores of stars and giant planets. Using the indirect drive approach, NIF was used to drive a gas-filled capsule implosion, heating capsules to extraordinary temperatures and compressing them to high densities where fusion reactions can occur.

“One of the most important findings is that we reproduced prior measurements made on accelerators in radically different conditions,” Casey said. “This really establishes a new tool in the nuclear astrophysics field for studying various processes and reactions that may be difficult to access any other way.”

“Perhaps most importantly, this work lays groundwork for potential experimental tests of phenomena that can only be found in the extreme plasma conditions of stellar interiors. One example is of plasma electron screening, a process that is important in nucleosynthesis but has not been observed experimentally,” Casey added.

Now that the team has established a technique to perform these measurements, related teams like that led by Maria Gatu Johnson at MIT are looking to explore other nuclear reactions and ways to attempt to measure the impact of plasma electrons on the nuclear reactions.

Casey was joined by co-authors Daniel Sayre, Vladimir Smalyuk, Robert Tipton, Jesse Pino, Gary Grim, Bruce Remington, Dave Dearborn, Laura (Robin) Benedetti, Robert Hatarik, Nobuhiko Izumi, James McNaney, Tammy Ma, Steve MacLaren, Jay Salmonson, Shahab Khan, Arthur Pak, Laura Berzak Hopkins, Sebastien LePape, Brian Spears, Nathan Meezan, Laurent Divol, Charles Yeamans, Joseph Caggiano, Dennis McNabb, Dean Holunga, Marina Chiarappa-Zucca, Tom Kohut and Thomas Parham from LLNL, Carl Brune from Ohio University, Johan Frenje and Maria Gatu Johnson from MIT and George Kyrala from LANL.

Abstract: Stars are giant thermonuclear plasma furnaces that slowly fuse the lighter elements in the universe into heavier elements, releasing energy, and generating the pressure required to prevent collapse. To understand stars, we must rely on nuclear reaction rate data obtained, up to now, under conditions very different from those of stellar cores. Here we show thermonuclear measurements of the 2H(d, n)3He and 3H(t,2n)4He S-factors at a range of densities (1.2–16 g cm−3) and temperatures (2.1–5.4 keV) that allow us to test the conditions of the hydrogen-burning phase of main-sequence stars. The relevant conditions are created using inertial-confinement fusion implosions at the National Ignition Facility. Our data agree within uncertainty with previous accelerator-based measurements and establish this approach for future experiments to measure other reactions and to test plasma-nuclear effects present in stellar interiors, such as plasma electron screening, directly in the environments where they occur.

Comments