Associate Professor Nicole Reynolds presented her work on Edmund Blunden in Paris and California

by Kristin M. Distel

Dr. Nicole Reynolds, Associate Professor of English and Women’s, Gender, and Sexuality Studies, gave two conference presentations on Alden Library’s Special Collections and the Edmund Blunden library in summer 2016.

Discovering Blunden

Blunden, a World War I poet, avid book collector, literary critic, and Oxford Professor of Poetry, amassed over 10,000 books in his personal library. Upon Blunden’s death in 1974, his widow sold the collection to Ohio University’s Alden Library.

“To have a collection intact like this is extraordinary,” Reynolds explains. “The collections of many authors, such as that of Siegfried Sassoon, are sold off piecemeal.”

Reynolds, who teaches undergraduate and graduate courses on the history of books and printing, recently developed a keen interest in Blunden’s collection. She presented her work, which focuses on an examination of Blunden’s marginalia, in Paris, France and Berkeley, California.

Promoting OHIO in Paris

The paper that Reynolds presented in France was titled “‘mark but the penning o’ it’: Paratextual Languages, Marginal Voices, and Idioms of Book-Love in Edmund Blunden’s Library.” The presentation was part of a conference on book history, hosted by SHARP: The Society for the History of Authorship, Reading, and Publishing. Reynolds’s attendance was financed by the College of Arts & Sciences Humanities Research Fund.

“The paper I presented in Paris grew out of my observations of Blunden’s books. In many of the books I was requesting, such as a first edition of Lyrical Ballads, the marginalia generated a narrative,” Reynolds notes. “I noticed Blunden’s ‘voice’ coming out of the texts.”

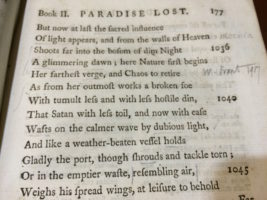

Reynolds examined Blunden’s notes in his copy of Milton’s ‘Paradise Lost’

“Using examples of Blunden’s marginalia, my paper demonstrated that Blunden interacted with books in ways that replicate patterns of reading and behavior common to Romantic readerships. Marginalia functioned as a social exchange in which Blunden demonstrated that he was conscious of his audience. I argued that marginalia is a way of continuing a conversation with authors and previous (anonymous) owners,” Reynolds explains.

Her Paris presentation also emphasized the surprising elements of Blunden’s marginalia. Reynolds was taken aback, she remarks, by Blunden’s personal engagement with some of the books in his collection, especially the instances in which Blunden seemed to hearken back to his experience as a soldier.

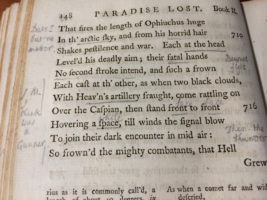

“Some of it was quite moving,” Reynolds states. She notes that Blunden’s copy of Milton’s Paradise Lost especially revealed the intersection between Blunden as a reader and as a survivor of war. “In reading the early books about the battle between God and Satan, Blunden was engaging with those scenes of war as a veteran who was actually in the trenches.”

Blunden’s notes point to his experience as a soldier, such as the annotation that remarks, “J.M. I think was a gunner”

In conducting research and reading Blunden’s marginal notes, Reynolds began to develop a sense of Blunden as a person and as a writer. “I started reading about him but also reading his poetry and prose,” Reynolds says. “Blunden is most famous for his memoir of World War I. In his memoir, he describes books that soldiers gave one another and further recalls finding books on the battlefield. He describes reciting poetry to his comrades. Knowing all this allowed me to emphasize in my presentation how very much books meant to Blunden.”

Bringing OHIO to Berkeley

The presentation Reynolds gave in California also highlighted her work with Blunden’s collection and his engagement with fellow writers. Reynolds delivered her paper, titled “‘A burning deathless discontent’: Edmund Blunden, John Clare, and the Legacy of the Great War,” at the meeting of the North American Society for the Study of Romanticism.

“This presentation focused on Blunden’s reading of John Clare, whom Blunden sees as a predecessor,” Reynolds notes. “I consulted books from Blunden’s collection to look at the way in which Blunden responds to Clare, to examine the similarities in their pastoral, rural, Georgic verses.” Reynolds’s paper focused on the ways in which Blunden’s marginalia reveals a conversation and relationship between these two writers.

Reynolds also examined Blunden’s marginal comments on John Clare’s poetry

“Blunden has given me a model for the type of writing I’d like to do,” says Reynolds. “He really thought about his work and his reviewing of books as ways of conveying to the public a sense of the value of literature, both past and present. He was a scholar; he composed academic editions of others’ work, and he taught at Oxford. Outside of that, though, he wanted to spread the conversation about books. He wanted to demonstrate that it could be a public good to read great literature.”

Shared Interests Among English Faculty

Currently, Reynolds is teaching a graduate seminar on the history of books and printing. A course the subject on has long been listed among the English Department’s offerings, but no one had taught it in years, Reynolds notes. Indeed, there is significant and increasing interest among English Department faculty and students in the history of books, personal libraries, and the ways in which publication of books has changed over the years. Associate Professor Beth Quitslund, for example, researches editions of the biblical Psalms and examines copies of 16th-century religious texts.

Additionally, Associate Professor Joe McLaughlin has long had an interest in book serialization and frequently asks students to read novels that were originally published in serial form. In fact, McLaughlin also introduced Reynolds to the work of Edmund Blunden.

“It’s a real instance of simpatico,” Reynolds notes. “We’re essentially interested in different areas of the same field.”

“Talking with my colleagues and reading what Blunden said about books made me more interested in books as physical objects,” Reynolds explains. “Many writers in my immediate field of Romanticism have thought a lot about this. Within Romanticism, there has been a lot of great scholarship that takes a book historical approach.”

Researching Rare Books and Blunden’s Papers

To further her expertise in the field of book history, Reynolds attended the University of Virginia’s Rare Book School in summer 2015. The program, according to the Rare Book School website, “provides continuing-education opportunities for students from all disciplines and skill levels to study the history of written, printed, and digital materials with leading scholars and professionals in the field.”

Reynolds also held a month-long fellowship at the Harry Ransom Center, housed at the University of Texas at Austin, where she was able to read Blunden’s unpublished letters and journals. “I sifted through the detritus of his life,” Reynolds says. “Learning book history has helped me understand Blunden’s appreciation of books and his deep interest in historical and current practices in book making and publishing.”

“I’ve learned that even though Blunden isn’t widely read today as Sassoon or Wilfred Owen,” she states, “he certainly wasn’t a marginal writer. In fact, Blunden completed the first critical edition of Owen’s work. I learned that his mission was to promote writers. In a way, he was one of the first recovery scholars.”

Indeed, Blunden also believed in and promoted the work of several female writers whose writing might have been lost to history. “Blunden recovered the work of Charlotte Smith and Mary Robinson,” Reynolds notes. “He was certainly interested in the recovery of female voices.”

‘Book History Made Me Feel Charged Up’

Reynolds has found that researching book history and presenting her work on Blunden to like-minded scholars and students has been profoundly invigorating.

“I have always loved old books in the way that we all do. But now, I have a new cultural and historical context for reading books. I’m thinking more deliberately about book history in my teaching. My training in book history has made me feel charged up as a scholar. It’s new and exciting! There’s something wonderful about being able to teach book history and being able to offer something new to the department.”

Comments