Third in a series on macro-evolution. In this article, Dr. Alycia Stigall discusses the fossil record of species biodiversity—and why it might be more important to protect “intermediate” species like the Arctic Fox than “specialist” species like the Polar Bear.

By Sara LaJeunesse

From Perspectives

Billions lie dead on the sea floor. Among the carcasses are dozens of species of small-shelled marine organisms called brachiopods, their tight-lipped expressions frozen in time.

Four hundred million years later, 9-year-old Alycia Stigall collects rocks from the banks of a stream across the street from her home. Later, she will spend hours poring through A Golden Guide to Fossils to learn more about the fossilized creatures she has found.

Two and a half decades later, Stigall, now Associate Professor of Geological Sciences, is using these brachiopods to investigate patterns of extinction and species formation over time, including during several of the major extinction events that have happened on Earth.

“There are always species going extinct and new species forming, but in the Earth’s past there have been a handful of events during which we lost a significant amount of diversity,” Stigall says. “Understanding what happened during these events may help us to be more proactive with our current conservation management plans.”

Is Extinction to Blame?

Stigall is particularly fascinated with the biodiversity crash that took place 375 million years ago during the Late Devonian Period, which spanned from 385 to 360 million years ago. Just prior to the crash, the Earth experienced a burst of new species formation. For example, the first forests fanned across the landscape and the ancestors of all modern-day four-legged animals began to walk on land. By the latter part of the period, however, things had taken a turn for the worse.

“Somehow, the environment changed, and we see this massive loss of species diversity in the fossil record,” she says.

But is extinction to blame for the crash, as so many researchers currently believe?

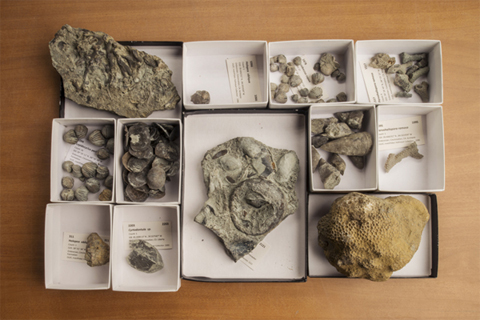

The Kallmeyer Collection of the Ohio University Invertebrate Paleontology Collections includes invasive species that dominated the ancient landscape of Cincinnati, Ohio. The invaders include brachiopods, gastropods, bivalves, and corals. (Photo by Ben Siegel.)

To find out, Stigall decided to pursue a hypothesis that had been proposed by George McGhee, Distinguished Professor of Paleobiology at Rutgers University, in the late 1980s: Even though extinction in the Late Devonian Period was higher than normal, it wasn’t the only cause for the decline. What was more important was a lack of new species formation.

“We all can easily understand how to drive a species to extinction, but how does one stop a species from speciating?” McGhee says. “Yet, at several critical biodiversity crises in Earth history, we see that the biodiversity loss was driven by the failure of species to continue to diversify, and it is important that we find out how this happens given our current ongoing biodiversity crisis.”

To differentiate the various species, Stigall uses a microscope to

analyze fine details of the shell structure. This allows the research

team to generate evolutionary trees for all species within a genus.

(Photo by Ben Siegel.)

To learn why speciation stalled, Stigall examines the physical characteristics of thousands of individual fossil brachiopods, as well as other invertebrates, such as clams. She notes the geographic location at which she found them and constructs phylogenetic trees, which indicate the evolutionary relationships among organisms. Her goal is to identify which species evolved into others and which ones went extinct.

Stigall’s research has shown that generalist species—those that are able to utilize a wide variety of food, habitat, and other resources—invaded the territories of specialist species—those that have very specific food, habitat, and other resource requirements. The specialists—including many species of brachiopod—couldn’t tolerate this new competition, and many of them went extinct. Yet what caused the biggest drop in diversity is not extinction, but rather a lack of new and distinct species formation.

“Generalists have much lower speciation rates than specialists,” says Stigall. “So when the specialists were knocked out, speciation went down the drain.”

By examining the rocks in outcrops around Cincinnati, Stigall found that the same thing happened 100 million years earlier during the Ordovician Period, which encompasses the interval from roughly 485 million years ago to 443 million years ago. During this time, no life existed on land, and fish were only just beginning to evolve in the oceans.

“It turns out that the fossils in rocks around Cincinnati help to develop the next piece of the invasive species story because they show that a dramatic invasion occurred right in the middle of the Late Ordovician,” she says.

According to Stigall, it took 1 million years for diversity levels to recover after the Ordovician species invasion.

This drawer of geological speciments contains nearly 20 species of the Vinlandostrophia brachiopod in Cincinnatian rocks. Some of the specimens were collected by Stigall and her students, but most were donated by Cincinnati, Ohio, resident Jack Kallmeyer, who donated the collection to the university. (Photo by Ben Siegel.)

The Arctic Fox Instead of the Polar Bear?

Fast forward to the present day, a time many scientists refer to as the Earth’s sixth mass extinction event.

“One of the things humans are great at is moving things around,” says Stigall. “Species like zebra mussels, which were brought into the Great Lakes in ships’ ballast water, are causing major shifts in ecosystem structure and threatening the survival of many native species. By understanding the long-term consequences of species invasions in the fossil record, we can better predict what will happen as a result of the current species decline.”

Stigall believes that in a few thousand years, the world will be occupied by mostly generalist species or species that are in between generalists and specialists—what she calls intermediate species. “I think we’re going to lose most of our specialists,” she says. “And I think it will take at least a million years to come back to a more diverse type of system.”

Stigall suggests that conservationists should focus their efforts on protecting the habitats of intermediate species because they have the greatest potential to be saved. Animals, like polar bears and cheetahs, she says, are such a problem because they are so specialized. Instead, it may be best to protect species, such as Arctic foxes, that are likely to have areas with future habitat impacts, but that fit the intermediate specialization type.

“I’m pretty optimistic about our species,” Stigall says. “I think that fundamentally we can solve our way out of a lot of these problems, we just have to get the will to do it. Eventually we’ll be all right; things will just be a little bit different.”

See It’s Time for a New Big Picture on Evolutionary Theory and Macro-Evolution: The Case of the Late Devonian Biodiversity Crisis)

This story appears in the Spring/Summer 2014 issue of Ohio University’s Perspectives magazine, which covers research, scholarship and creative activity.

Comments