By Rachel Thomas

Honors Tutorial College student studying Classics in Rome

Rome, perhaps more so than other cities, has a rich mythic history, the presence of which is felt even today. A stroll down one of the many winding pathways may easily lead you to bars with names like caffe Enea, named after Aeneas who, with his aged father and young son, escaped the ashes of Troy in order to eventually produce a family line leading to Romulus and Remus, the former of whom gave his name to the city itself. Similarly, restaurants and hotels named after historical figures are common, especially in the portions of the city closest to ancient remains. While the tourist-filled areas result in the anachronistic presence of faux-centurions, even the quieter areas around Rome are deeply conscious of their mythic past.

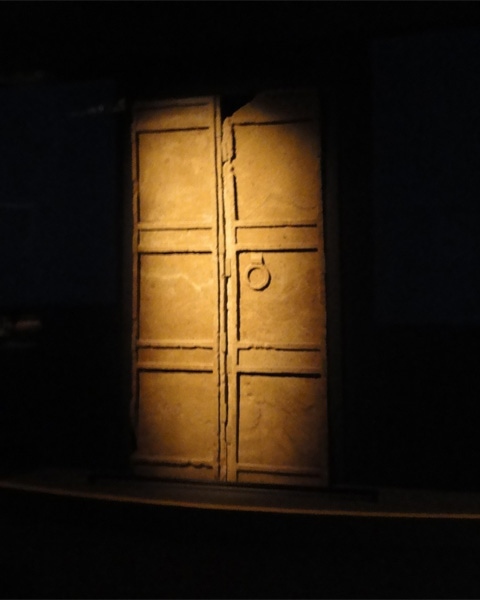

Although modern realism would have us point out the fictive nature of this history, and the Romans largely did the same, there are many rich, valuable things one can learn from observing the nature of this historio-mythic collection and the way that it influences modern Roman culture even today. Throughout the past four weeks, I have found that using extant sites within Rome and the greater area of Latium as a kind of Roman Bifrost—a tangible connection between two worlds, one mortal and one (for our purposes) mythic—serves to cement connections between material culture, literature, and the all-too-human drive to tell stories.

As a student of literature both fictional and non-fictional, I find that one of the most telling features about a culture or a person lies in the kind of story they appreciate or find important. This holds true for the ancient world, in which some of the greatest myth becomes deeply entangled with politics and propaganda as well. Virgil’s Aeneid, picking up narrative threads first woven by Homer in the Iliad, is perhaps the most famous example: although written under Caesar Augustus and featuring a number of elements identifiable with the changing political scene, it is moreover a beautiful work of Roman poetry. While it is true that a number of features about the way that Virgil characterizes Aeneas and other figures in the poem—for instance, the characterization of Aeneas as pius, from which our term “pious” naturally descends—are easily linked to Augustan propaganda, a number of these features are really inherent within Roman society and values as a whole. Rather than Augustus deciding that pietas (the Roman virtue of piety, which encompassed proper behavior in a variety of ways) was worth promotion, Augustus made use of the preexisting conception of pietas—a vital quality in, for example, the way that Romans thought about the mythic origin of their line.

This attention to certain methods of characterization is still clearly demonstrated in extant ruins. From the faint remains of the so-called Heroon of Aeneas to the depictions of many an emperor in his role as pontifex maximus (still playing into the imagery of pius Aeneas), one can witness the physical manifestations of certain ideas and concepts that reach from Roman storytelling and the realm of the mythic into the very real world of history and archaeology. Although some are tempted to dismiss the mythic qualities of Roman history, these qualities are vital to understanding how the Romans thought of themselves and their position within the world. Through studying their myths and stories and the material remains of these narratives, we can come to a better understanding not only of the ancient people, but of our own narrative inclinations as well.

Comments