Earth Day Quiz: Eastern Deciduous Forest (True/False)

- Forest cover is at the lowest level since European settlement.

- Native Americans and Smokey the Bear both tried to keep forest fires from starting.

- Forests are changing because of drought conditions caused by climate change.

- Passenger pigeons may have been helpful to oak trees.

- The most important tree in the forest is the oak

Geographer Reaches into History for Answers

If Paul Revere rode his horse from Boston to Ohio today, he might have a new message: The maples are coming! The maples are coming!

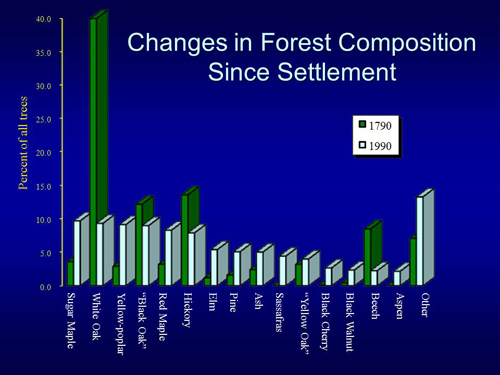

Move over majestic oak trees. Red maples are now the most important trees in the forest.

In the 200 years or so years since the American revolution, another revolution has been under way—in the deciduous forests of the eastern North America. Many forests that used to be dominated by oaks are now ruled by the red maple.

Biogeographer James Dyer wants to know why. And some of the answers are surprising.

True/False: Forest cover is at the lowest level since European settlement.

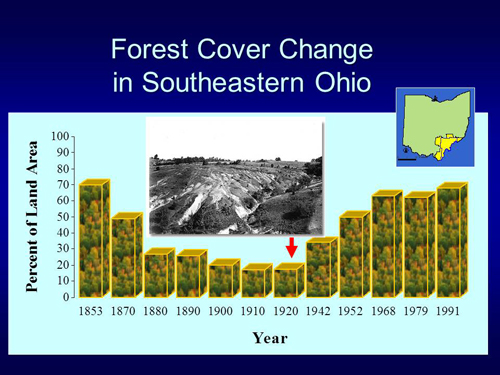

“It is said that before European settlement, the East was almost completely forested, and a squirrel could travel 1,000 miles inland and never touch the ground,” says Dyer, a Professor of Geography in Ohio University’s College of Arts & Sciences. “Today, forest cover in eastern North America is about 40 percent.

“But forest cover has actually been increasing since the mid-point of the 20th century,” he says. “Previously cleared land is now regenerating into new forest.” In his research, Dyer takes a look at the historical ecology of the forests. With more than a decade of fieldwork and archival analysis, he examines disturbances in the forest canopy, climate change, wildlife changes, and the effects of clearing—with some interesting discoveries.

“We experienced a very rapid and widespread clearing of forests in the last 200 years. What effect did that have on our forest?” he asks. “The oak-to-maple transition” is the most important.

A walk through the Ridges Land Lab at Ohio University illustrates the situation: There are still majestic white oaks, but the forest floor is awash in small maples. The oaks are not regenerating.

True/False: Native Americans and Smokey the Bear both tried to keep forest fires from starting.

One commonly cited factor in the red maple revolution is forest fires. Fewer forest fires, that is.

“The dominant view has been is that it’s caused by the cessation of frequent burnings by native Americans Native Americans used fire extensively, which promoted oaks, and 20th century fire suppression is favoring maples and other species. That stopped, and now we’re seeing the transition.”

“No doubt native Americans did use fire as a management tool,” Dyer said, as indicated by this quote from southeastern Ohio about a fire in the Marietta vicinity in 1788:

“Yearly autumnal fires of the Indians, during a long period of time, had destroyed all the shrubs and undergrowth of woody plants, affording the finest hunting grounds,” wrote Samuel Hildreth.

Evidence and support for the view that fewer fires help the maples:

- Oaks are promoted by surface fire, maples are less fire tolerant.

- Oaks’ thicker bark insulates against fire. Maples have thinner bark.

- Oak seedlings build larger root systems, which are safe from fire.

- Oaks need more light, are less shade tolerant than maples, indicating a need for canopy-opening disturbances such as fire.

“One question though,” says Dyer, “is how extensive this practice was through all of eastern North America. We don’t know too much about what pre-settlement fires were like, but we have a big peak in post-settlement fire and land-clearing, followed by the suppression era—the Smokey the Bear era.”

Today, prescribed burning is an active management tool used on most public lands, trying to get oaks to regenerate, but the results are not clear. “So we don’t want to lock ourselves into one explanation, when potentially it could be a number of factors,” he says.

True/False: Forests are changing because of drought conditions caused by climate change.

“If it’s not solely fire, what else could it be?” Climate change is a possible answer.

Dyer and his colleagues looked at climate reconstruction based on tree rings. The tree rings showed very wet conditions in the 20th century, compared to extreme droughts in preceding centuries.

“If we don’t trust the tree rings, we can look at the instrumental record and we get a similar story, so we have a change in climate coinciding with this change from oaks to maples. “Could oaks be more adapted to drought, maples to wet conditions?”

The third factor that Dyer examined was the “biotic interactions,” in particular passenger pigeons and white-tailed deer.

True/False: Passenger pigeons may have been helpful to oak trees.

“In the mid-1800s, the passenger pigeon population was estimated at 3-5 billion. And when they would flock in the central hardwood forest, there would be so many birds that they would just break the branches and open up the canopy, allowing more light,” Dyer says. This kind of disturbance, falling trees and branches, helped get needed sunlight to oak saplings.

White-tail deer, on the other hand, have gone from scarcity to overpopulation, to the likely detriment of the oaks. “By 1900, it’s estimated there were only 1-2 million deer in all of eastern North America. Their numbers have skyrocketed since that time. We know when you have too many deer they are going to over-browse, and they like oaks, so they are going to preferentially browse oaks. And they eat a lot of acorns in the fall. Their numbers are changing, and that could have an influence on the oak to maple transition,” says Dyer.

Another question to think about: “Is it just the clearing, or is what we do on that cleared land important? Do specific land-use practices leave distinctive ‘signatures,’” asks Dyer.

True/False: The most important tree in the forest is the oak.

“One last thought about forest cover. If we go back to southern Ohio about 1800, there is probably about 90 percent or more forest cover. By the 1850s, the canals are completed. By 1880, the railroads are in, so we’re opening up land. We’re seeing clearing increase dramatically, bottoming out around 1920, and then reforestation begins.

“So we’re heavily forested today. But these forests today are very different from the forest of the 1800s. We know there’s been a change.” Dyer turned to historical land use records to help determine if using cleared land for pasture or tilling had distinct effects. “The tax collector, for example, documented how much land was in cultivation, how much in forest, and how much in pasture. Aerial photography started in 1938, so we can actually see what’s happening.”

Dyer used three classifications of presently-forested sites:

- Never cleared—“continuously forested”

- Cleared but used for pasture

- Tilled or cultivated

He sampled both trees and the herbaceous layer. “In terms of the trees, no real surprises,” he says. “When we clear the trees, it favors rapidly dispersing, fast growing species. So confirming what we’ve been talking about.” Today’s forests are young, most less than 90 years old, with an increase in early successional species that disperse very well such as black cherry and sassafras, as well as shade-tolerant species such as maple.

“Oaks have declined. Maples have increased. And a lot of other things are happening simultaneously,” concludes Dyer. “The climate is wetter now than it was in the past. We pretty much cleared our forests, and now they have regenerated. Wildlife numbers are changing dramatically simultaneously. These are multiple interacting drivers in the forest regeneration. But we have to think about what went on in the past—200 years of history—to understand what’s going on there in our contemporary forests.”

View video of Dyer’s research on the oak-to-maple transition.

Quiz answers: F, F, F, T, F

Comments